Introduction¶

In this section we’re going to talk in a bit more detail about neuromorphic computing. That is, nonstandard computational architectures that mimic some aspect of the way the brain works. That doesn’t have to mean spiking, but a lot of recent approaches do use spiking activity in some form. There have been a lot of approaches to designing neuromorphic computing devices. One review paper included 2,700 references, 66 pages out of an 88 page paper. So there’s no way we can cover everything that has been tried. Instead, we’re going to give an overview of some of the most common features, highlighting a few examples, and suggest you go take a look at the extensive literature if you want to know more!

Overview¶

Let’s start with a rough outline of some of the parts that tend to be involved.

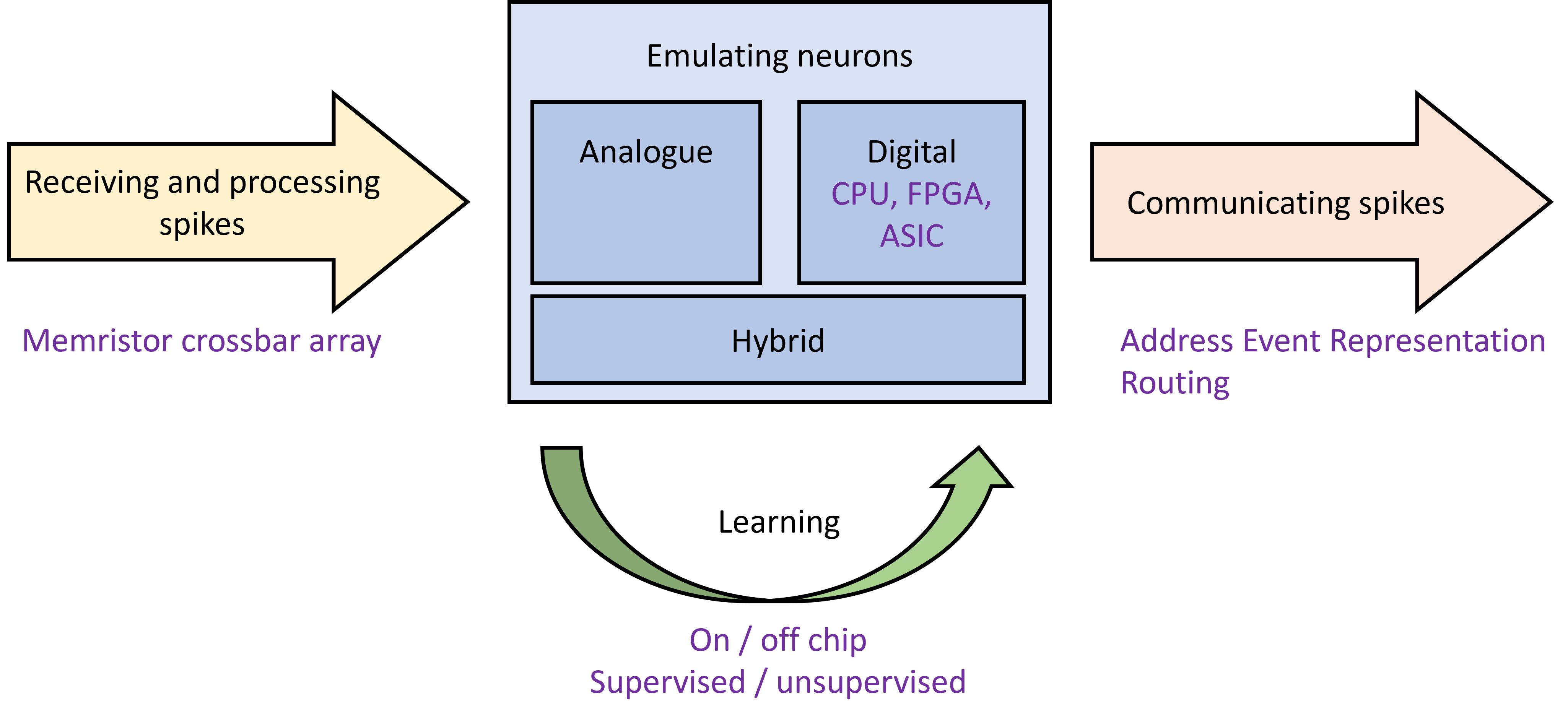

Figure 1:Neuromorphic computing overview.

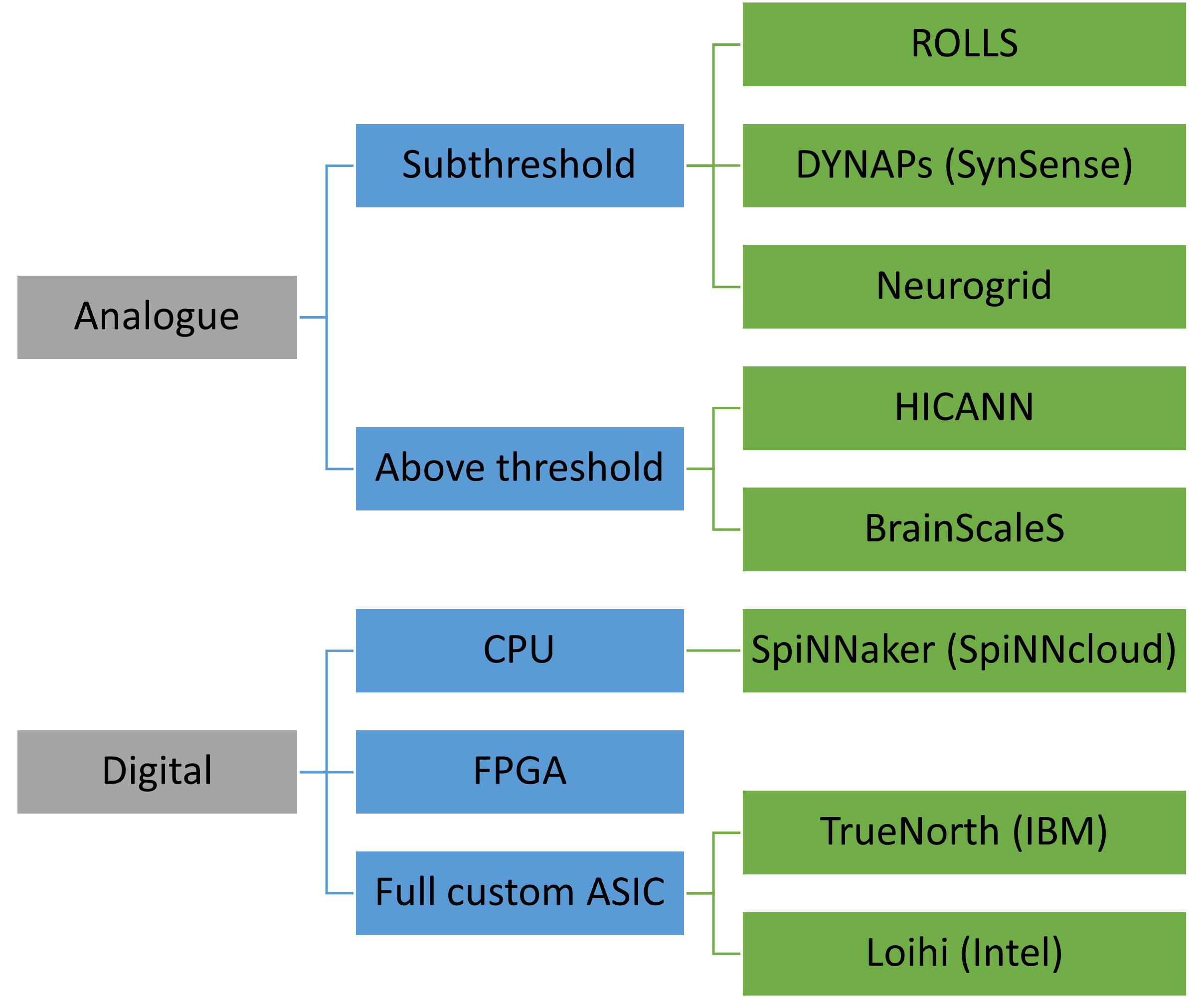

At its core, there is some technology to emulate the function of neurons. That could be an analogue process, where new materials or circuits are designed that can mimic the dynamics of neurons. Or it could be a digital process based either on traditional CPUs, or on newer hardware fully or partially customised to handle simulating neuronal dynamics and spikes. It can also involve a combination of both approaches.

This hardware has to have a way of processing a potentially very large number of incoming spikes, and a common approach is the memristor crossbar array that we’ll talk about later.

There also needs to be a way for a neuron to communicate its spikes to other neurons. There’s a standard protocol for that - the address event representation (AER) - and a few different approaches to routing spiking events efficiently to their targets.

Finally, there’s learning. Ideally, this should be done on the neuromorphic device itself for maximal efficiency, but that’s not always easy to arrange and so often training has to be done inefficiently off chip, with only the forward or inference pass done on the chip. As with all learning, there are supervised and unsupervised approaches and both have been tried with different types of neuromorphic device.

Emulating neurons¶

The first step is simulating the neuron or components of the neuron. A very traditional approach that goes back to the beginning of neuromorphic computing is subthreshold analogue approaches. In these, you design an electrical circuit that behaves like a neuron model, with time constants that are comparable to biological ones so that it can operate in realtime.

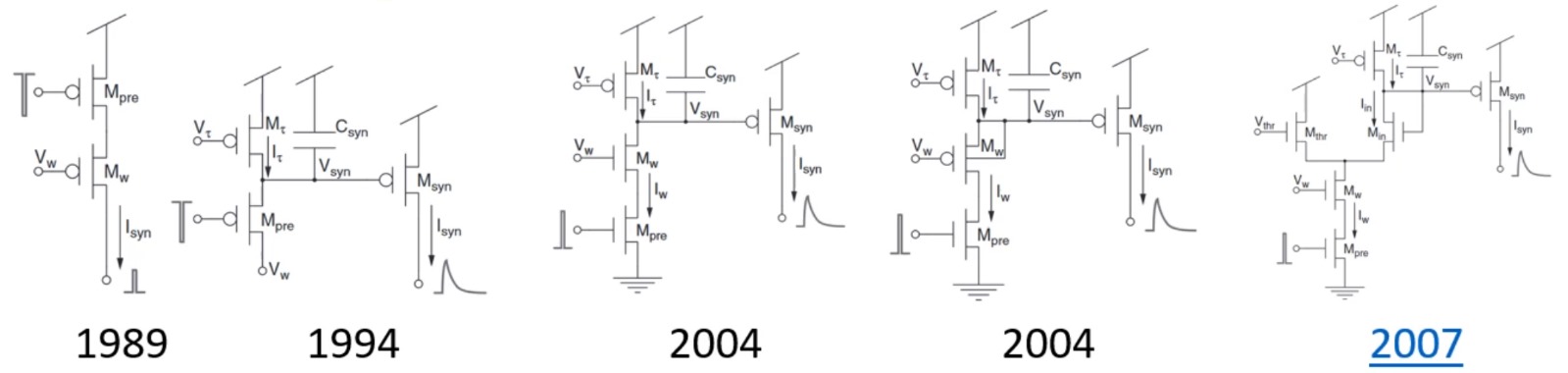

Bartolozzi & Indiveri (2007) shows a series of increasingly complicated circuits built with a transistors and capacitors that over time more and more closely emulate synaptic dynamics.

Figure 2:Transistor / capacitor circuits designed to emulate synaptic dynamics Bartolozzi & Indiveri, 2007.

There are also above threshold analogue approaches that are thousands to hundreds of thousands of times faster than biology, and so they can be used for accelerating simulations. On the downside, they tend to have higher currents and more complicated circuit designs.

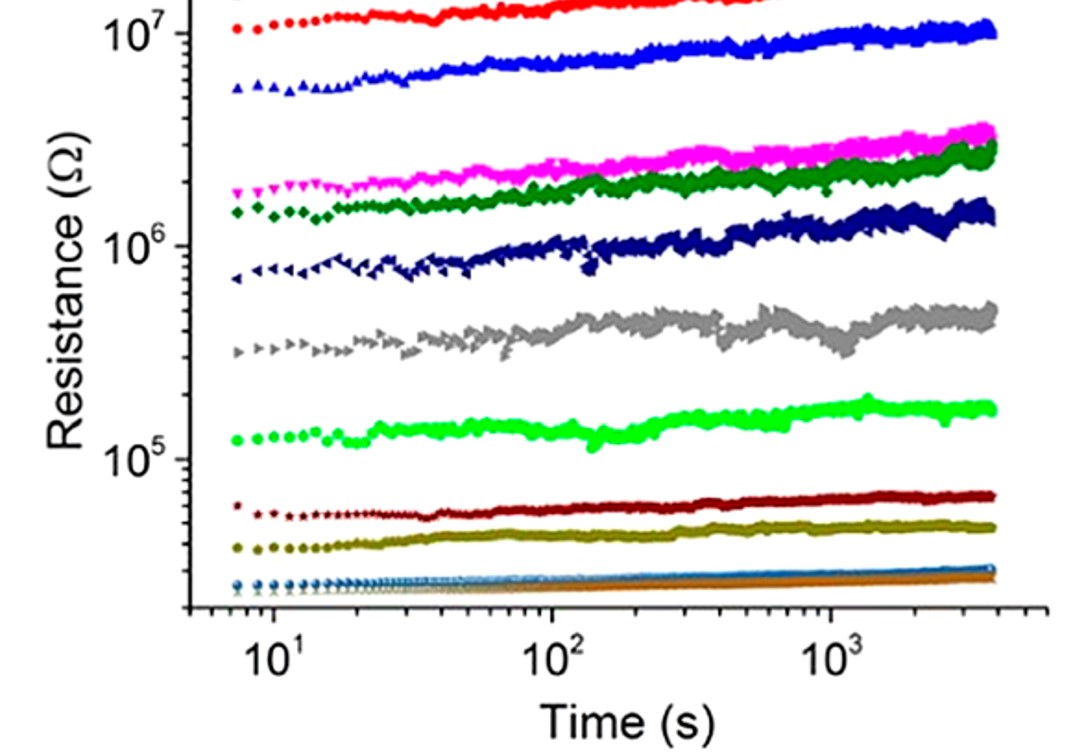

It’s worth noting that these analogue circuits are noisy, for example here you can see how conductances change over time with one of these technologies. This is something we have to take into account but it may not be a problem if the underlying network is noise robust, like the brain.

Figure 3:Conductance change over time in neuromorphic device Bartolozzi & Indiveri, 2007.

Then we get to digital approaches. The simplest of these is just to use a standard CPU, for example a reduced instruct set processor like an ARM. The clever part is in connecting these together. This approach tends to be very flexible in terms of what you can simulate, but less power efficient than more customised approaches.

FPGAs are a first step towards full customisation. They allow for partial configuration of the hardware. They’re a bit less flexible than a CPU but can also be more efficient in terms of speed and power.

Finally, you can go all the way to fully customised chips. These are the least flexible and the most expensive to develop, but can be much more efficient. And of course there are also hybrid approaches that combine these elements in different ways.

Receiving and Processing Spikes¶

Once we’ve emulated the neuron, we need a way to receive and then process incoming spikes.

The key problem here, which is common to both artificial and spiking neural networks is the matrix vector multiplication.

This is typically the most expensive part of a neural network simulation, so speeding that up or reducing its power consumption is a critical part of the design of a neuromorphic system.

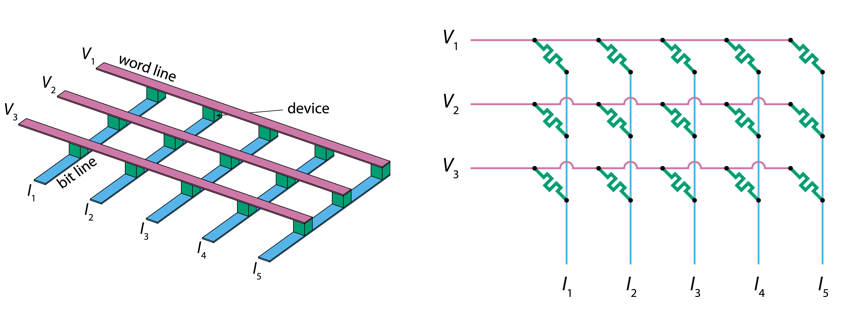

A common solution is the memristor crossbar array. A memristor is an electrical component with a programmable conductance. If you connect them in a grid like in these diagrams, you can use it to implement this matrix vector multiplication. The rows are the inputs represented as voltages, and the columns are the outputs represented as currents. At each grid point, you have a memristor whose conductance represents a synaptic weight. The current at a grid point is the product of the input voltage and the memristor conductance. The total current output of a column is the sum of the grid point currents, which is exactly the computation you need for matrix-vector multiplication.

Figure 4:Memristor crossbar array Joksas & Mehonic, 2020.

Sending spikes¶

In addition to processing spikes that have been received, we also need to send spikes. The way the brain does that is simply to have one wire from each input to each output. Can we just do the same? Yes, but if you have N inputs and N outputs you need wires which is expensive, especially when chips are limited to 2D unlike the 3D brain.

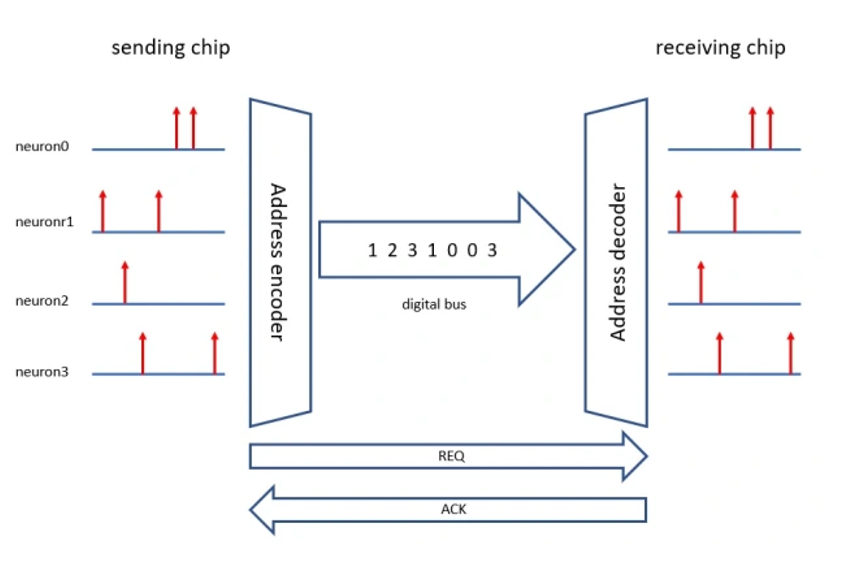

Another way of doing it is the address event representation (AER) scheme. In this scheme, each input event is first encoded in binary, and this needs bits.

Those events are communicated by multiplexing them in time on a very fast digital bus. A routing table allows you to dispatch these events to their targets, which can then reconstruct the input spike trains. This only needs a number of wires proportional to which is much better.

Figure 5:Common AER scheme in neuromorphic systems (source).

However, because multiple events may happen simultaneously, you either have to queue simultaneous events, introducing an error in time, or drop them entirely. This is theoretically problematic if your aim is a perfect simulation, but not necessarily a big issue if you have trained a noise robust network using some form of temporal jitter and synaptic dropout.

This AER scheme is therefore very widely used in neuromorphic systems.

Learning¶

The final ingredient we need is learning. The easiest thing to do is just to do the learning off the neuromorphic device and copy the synaptic weights and other parameters across. This is very flexible because you can do any learning rule you like with this approach. But it means you lose the benefits of simulating it on the neuromorphic device, and that often puts a limit to scaling.

The other approach is to do the learning on the chip itself. This is ideal from the point of efficiency, but it has some downsides. We can’t use global gradient information, which rules out learning rules like backprop through time used in surrogate gradient descent. In a way this shouldn’t be a problem because the brain also doesn’t have access to that information and must use a local learning rule. But even if the brain knows how to do learning with local information only, we don’t yet know how to do it as well as with global information. Also, this local information needs to be managed and transmitted to the right places, and so this has to be incorporated into the hardware design, limiting flexibility.

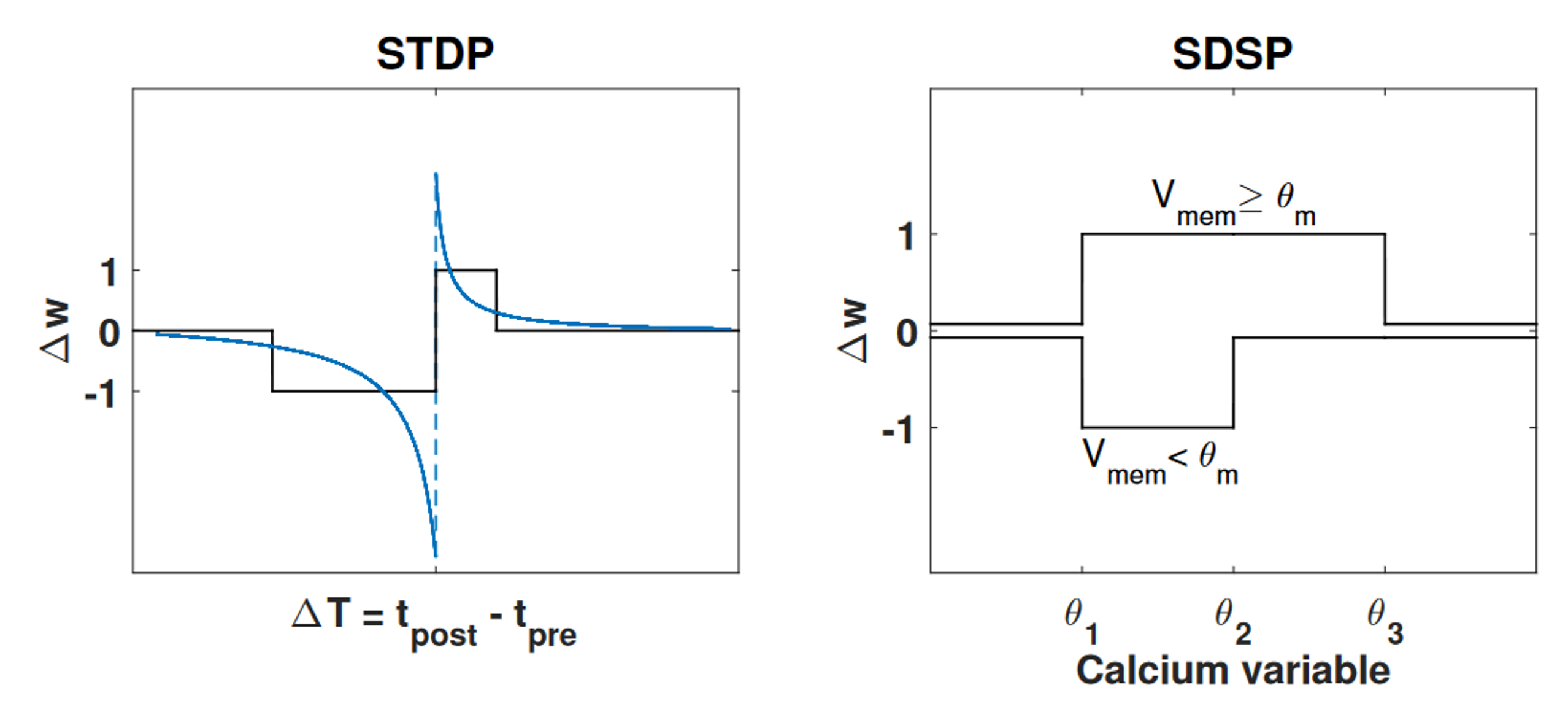

In practice, we often use STDP or an approximation of it, or a variant called SDSP (spike dependent synaptic plasticity). These rules are unsupervised which is a limitation if you want to train on a classification or regression task. But, you can restore an element of supervision using eligibility traces, which we won’t go into here.

Figure 6:STDP vs SDSP.

In some ways, learning is the big missing part of the neuromorphic computing story, and probably for the same reason that we don’t yet understand how the brain does learning with only local information.

Systems¶

Let’s finish this section with a quick look at some of the products available today, and how they use some of the components we’ve seen so far. As before, this isn’t an exhaustive list!

We’ll start with the analogue, subthreshold systems that run in realtime. The first is ROLLS and DYNAPs, now commercialised by SynSense. The basic ROLLS chip has 256 adaptive exponential integrate and fire neurons per chip, with 64k synapses with short term plasticity, and 64k using the SDSP learning rule. That goes up to thousands of neurons in DYNAPs and a spike routing architecture.

There’s also Neurogrid which has a million neurons but the synaptic weights are stored off chip, adding latency.

Next we have the above threshold designs that can run faster than realtime. There’s the HICANN chip with 512 adaptive exponential integrate-and-fire neurons and 112k STDP synapses with 4 bits per synapse.

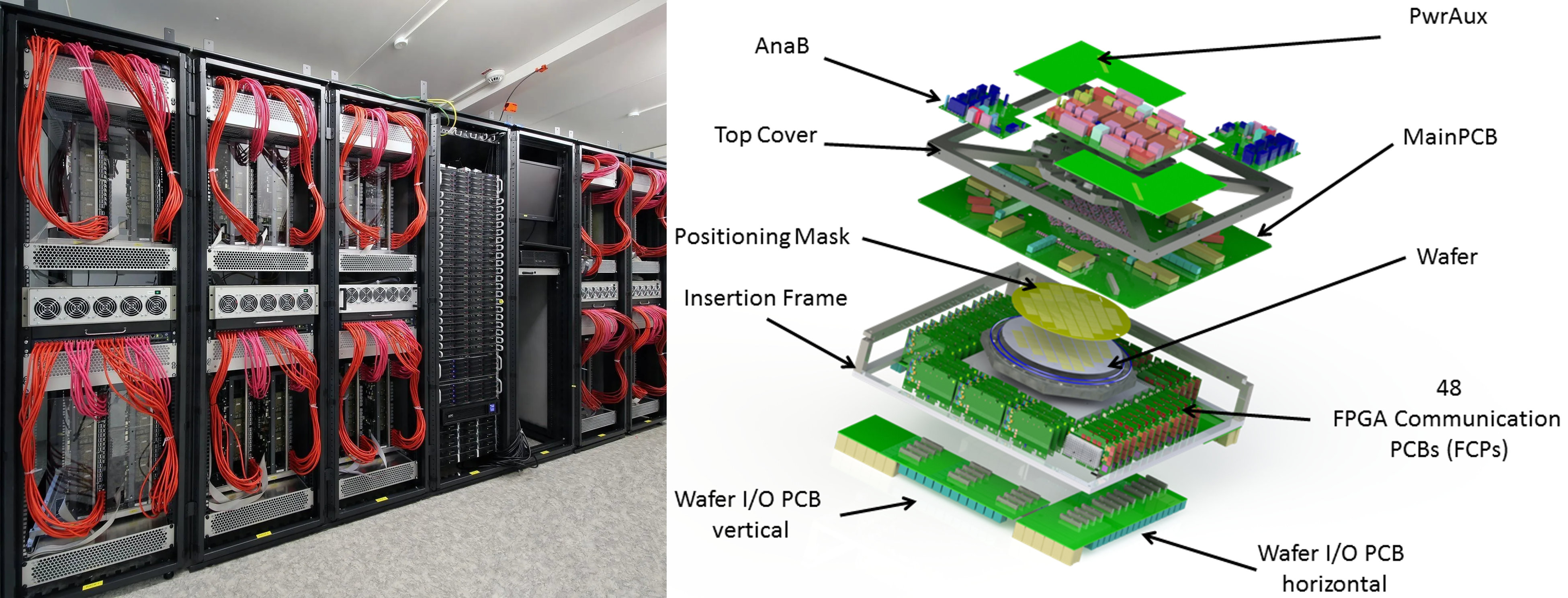

BrainScaleS consists of 352 of those chips, so 180k neurons and 40 million synapses per wafer.

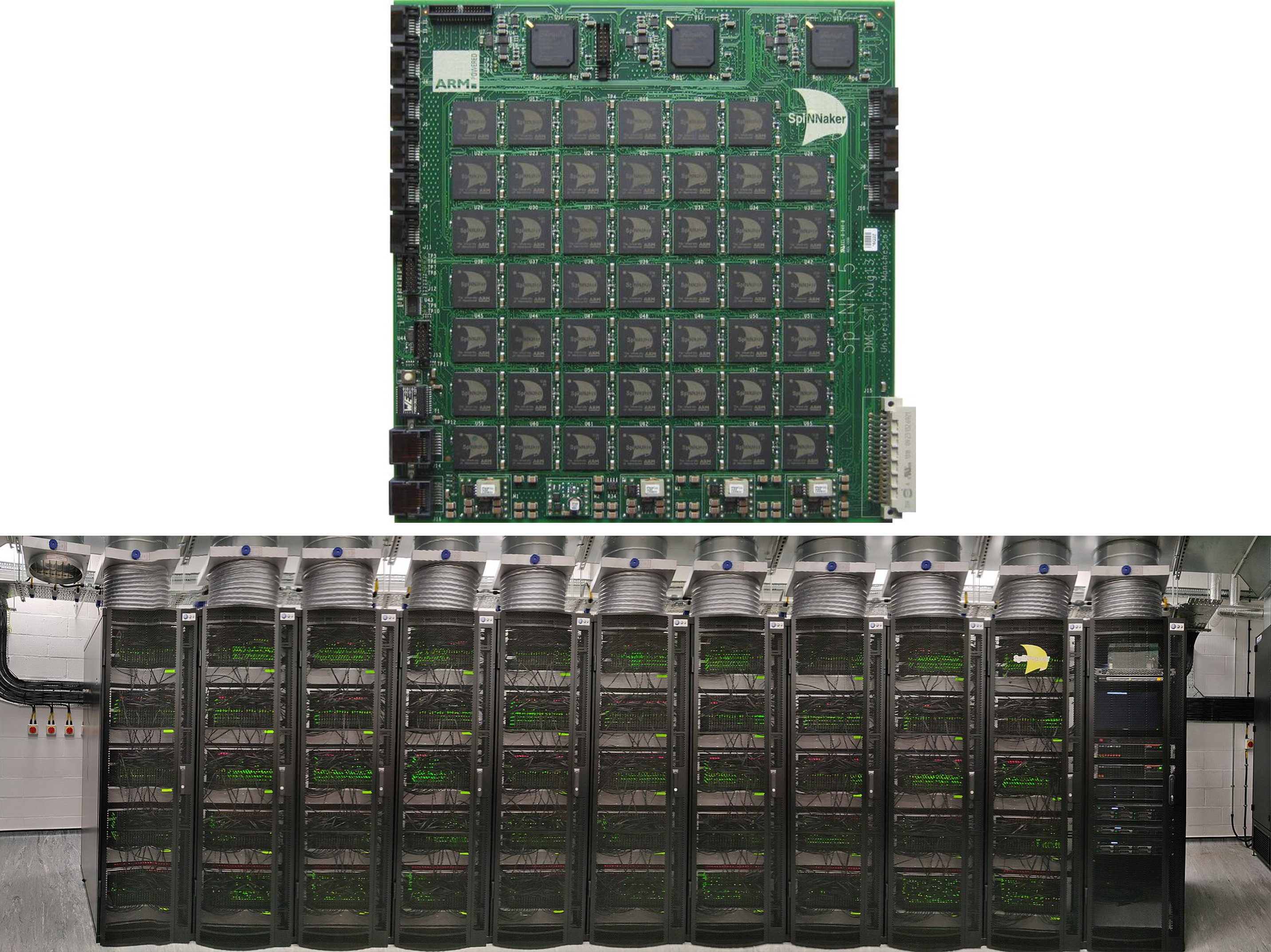

Next we have the digital designs, starting with CPU-based. SpiNNaker was originally designed by Steve Furber in Manchester, the same Steve Furber who designed the BBC Micro and the ARM 32-bit RISC chip. Given that background, it’s perhaps unsurprising that SpiNNaker works by combining a very large number of ARM chips, connected by a clever, high capacity event routing system. Because it uses general purpose CPUs it’s very customisable, although that does come at a relatively high energy cost. The first SpiNNaker system was scaled up to a million cores, 7 terabytes of RAM and could simulate a billion neurons in real time, about 1% of the human brain. Unfortunately, it did also draw about 100 kW of power. It’s being followed up by SpiNNaker 2, commercialised by SpiNNcloud, which aims to build a system 100 times larger, in other words able to simulate as many neurons as the human brain.

We won’t mention any FPGA-based systems although this has been investigated, including by researchers here at Imperial College.

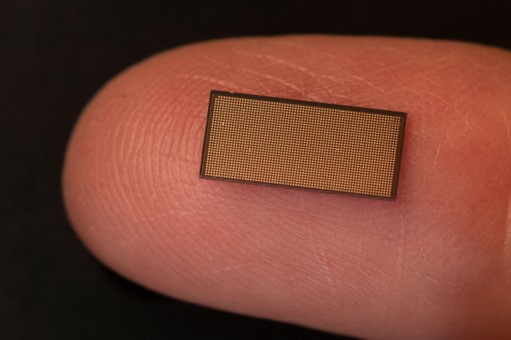

Finally there’s the fully customised chips being invested in by big chip companies. IBM’s system TrueNorth can simulate a million neurons and 256 million binary non-plastic synapses per chip, with a fixed neuron design. Just to give an idea of the energy efficiency gain of the custom chips versus general purpose, TrueNorth uses about 25 picojoules per connection, whereas SpiNNaker uses around 10 nanojoules, or about 400 times as much energy.

Intel’s Loihi has 180k neurons per chip, and synapses can be from 114k with 9-bits per synapse to 1M with 1 bit per synapse. They have a configurable neuron model and an open source toolbox called Lava that has encouraged many researchers to try it out.

There are many more systems out there, but we just wanted to give a quick run through of how some of the technologies we’ve gone through in this section are in production systems being applied to real world problems.

- Bartolozzi, C., & Indiveri, G. (2007). Synaptic Dynamics in Analog VLSI. Neural Computation, 19(10), 2581–2603. 10.1162/neco.2007.19.10.2581

- Joksas, D., & Mehonic, A. (2020). badcrossbar: A Python tool for computing and plotting currents and voltages in passive crossbar arrays. SoftwareX, 12, 100617. 10.1016/j.softx.2020.100617