Introduction¶

This week we’re going to be talking about neuromorphic computing, which is the use of specialized hardware that either directly mimics brain function or is inspired by some aspect of the way the brain computes.

A lot of the research for this week’s videos was done by Gabriel Béna who is currently doing a PhD with Dan.

Power consumption¶

Let’s start by talking about one of the major reasons why neuromorphic computing is capturing a lot of attention at the moment - electrical power consumption.

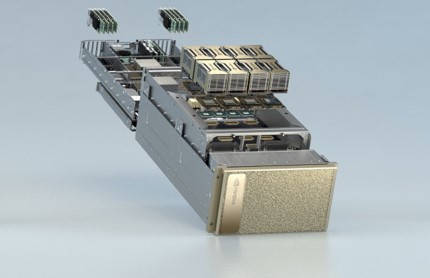

In 2023, ICT is estimated to be using around 10% of the world’s electricity supply, leading to around 2-4% of global CO2 emissions. That’s growing at an average rate of around 2 to 3% annually, and so clearly at some point something is going to have to give. Part of the growth is due to the increasing demands of machine learning applications. You can see here this NVIDIA DGX GPU server running 8 A100 GPUs draws around 6.5 kW of power.

Figure 1:NVIDIA DGX A100 with a power consumption of 6500 W.

The idea of neuromorphic computing is to take inspiration from the brain which we know is very power efficient. The human brain uses at most around 20 W, probably a lot less because that includes the energy required to keep the head warm and things like that. With that 20 W, it can do a lot of very sophisticated computation, including many tasks at a much higher level of performance than machine learning systems that require orders of magnitude more power.

Figure 2:Human brain: power consumption of W.

Or consider the brain of the honey bee which uses around 10 microwatts, enough to let it do sophisticated navigation, pattern recognition and social communication.

Figure 3:Bee brain has a power consumption of W.

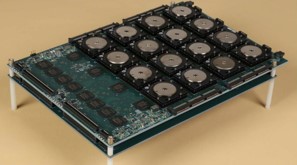

As an example of how neuromorphic hardware can reduce power consumption, you can see here IBM’s SyNAPSE chip from 2008 that did a video processing task using only 70 milliwatts.

Figure 4:IBM’s SyNAPSE chip from 2008 with a power consumption of 70 mW.

Limitations of standard computational hardware¶

It’s not only power consumption we can improve on. The standard paradigm of computing is beginning to show its limitations, and neuromorphic computing is one of several ideas that have been proposed to address some of the issues.

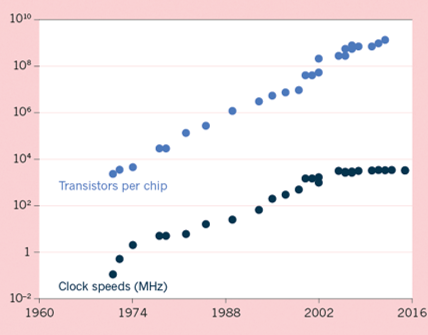

One thing we’re already starting to see is the physical limits to the exponential growth in computing power encapsulated in the famous Moore’s law. Indeed clock speeds which used to be the key metric of computational power stalled in 2004.

Figure 5:Moore’s law.

We’re also seeing that very often the bottleneck for accelerating code is memory bandwidth rather than compute. If you’ve done any GPU coding you’ll know that the whole game is about making sure that the massive number of cores get fed with enough data so they aren’t just waiting around. You can also think about mobile devices that don’t have the power budget to run full scale machine learning models. In that case, they become limited by the network bandwidth to communicate with a more powerful server.

Approximate computing is an interesting development that can solve some of these issues. The idea is that if you allow for noise in your computations, you can do some things that would otherwise not be possible. For example, if you don’t mind random bit flips where a 1 randomly changes to a zero or vice versa, then you can hugely reduce the voltage and therefore the power consumption, and run at much higher clock speeds.

If you have noise robust computations, there are many clever optimisation tricks you can play in terms of both hardware and algorithm design. But the key is, to enable all that, you need to have noise robust computations, and that’s very often difficult or unnatural for us. Neuromorphic computing is a nice approach to some of these issues. Firstly, since memory and compute are physically co-located, some of the bottleneck issues can be reduced. This is both true on device, and for mobile devices you can run some computations locally to avoid sending data to a server.

Algorithms are naturally noise robust because they’re brain inspired, and the brain is incredibly noisy and noise robust. This allows for many of the approximate computing aims to be realised. And finally, the whole system is naturally event based and asynchronous, which again allows for all sorts of clever optimisations that wouldn’t be possible on a system that guarantees operations are carried out in a fixed and deterministic order.