In the last section this week, we want to talk about some of the challenges for machine learning and for neuroscience, and how we think these two fields can help each other to make progress.

Power efficiency¶

Let’s start by talking about power efficiency.

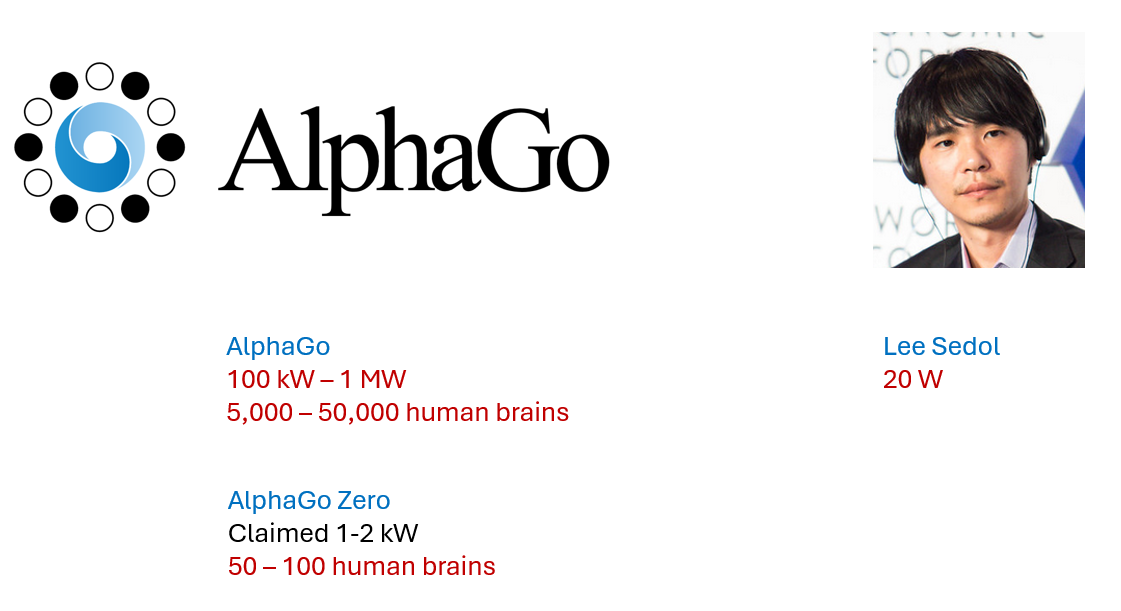

We’re going to illustrate this by talking about the famous Go match between AlphaGo and Lee Sedol.

To set the scene, computers overtook humans at chess in 1997, but in Go, a game with a much larger search space, humans remained superior. Until 2016 when DeepMind’s AlphaGo beat top human player Lee Sedol.

In that match, it has been estimated that AlphaGo was drawing somewhere around 100 to 1000 kilowatts of power, compared to presumably around 20 W for Sedol’s human brain.

That means AlphaGo was around 5,000 to 50,000 times less efficient than a human brain, and it’s worth saying that the human brain was also doing a bunch of other stuff at the same time.

Obviously that’s a huge difference, but this might be overstating the case a bit.

By the next year, DeepMind had implemented AlphaGo Zero which played better than the previous version and they claim was only drawing around 1-2 kilowatts of power, so only about 50-100 human brains.

Still very inefficient, but it only took a year to improve by a factor of 50 or more, so I wouldn’t bet against the machines on this.

Sample efficiency¶

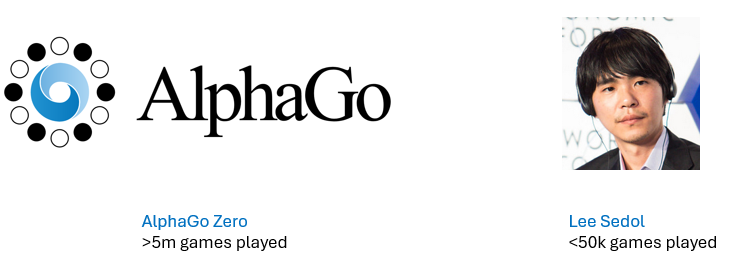

There is another challenge for machine learning though, which is how much training it needs to reach high levels of performance.

AlphaGo Zero was trained on over 5 million games.

We don’t know how many games Lee Sedol played, but at the time of that match he was 33, and assuming he started playing at age 5 and played 5 matches a day every day from then on, he would only have played around 50,000 games.

That’s not entirely fair of course because he was making use of the collective knowledge of all humans who have ever played this game. But then AlphaGo was also able to use this and it turned out that it didn’t help very much.

The training was a little faster, but it actually capped out at a lower performance at the end of training.

Generalisation and re-use¶

One of the reasons for this is that humans have a lot of knowledge they can call on and use in new scenarios, and machine learning methods still lag behind in this - although progress is fast.

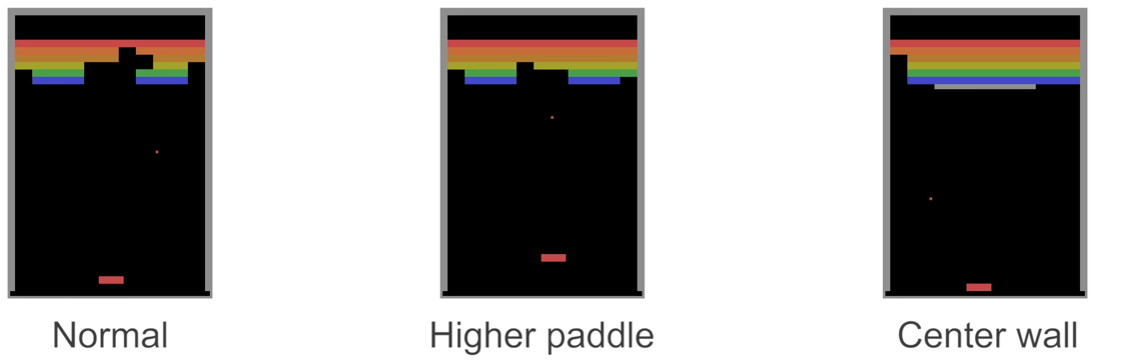

To illustrate this, in 2016 the company Vicarious - later bought by Google - had an interesting analysis of the game Breakout.

You know the game where the ball bounces around, and you control the paddle that moves left and right and you have to destroy all the coloured bricks at the top by hitting them with a ball.

Well it turned out that the state of the art deep RL methods of the time were easily able to master this game, but then they started introducing variations.

If you just move the paddle a bit higher, a human player has no problem at all adapting, but the deep RL agent needed to be retrained almost from scratch.

Similarly, adding an unbreakable wall in grey.

Figure 1:Paddle game test cases for human vs machine retraining (see Vicarious 2016 on schema networks and Kansky et al. (2017))

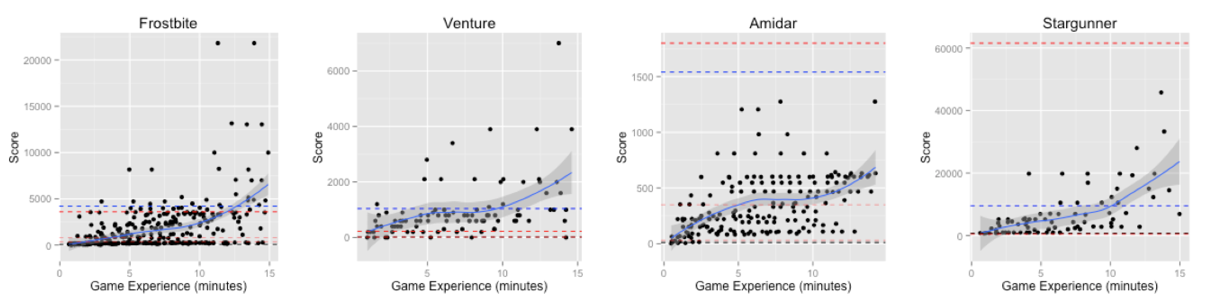

Another example is an analysis of human learning of Atari games that were famously mastered by deep RL.

This study found that for some of the games, in under 15 minutes of training, humans could learn to play at a similar or better level than the deep RL agents after tens or even hundreds of hours of play.

Figure 2:Learning curves for humans vs machine in Atari games (paper).

Robustness¶

The last challenge we want to talk about for machine learning in this section is robustness.

Although the situation has improved recently, machine learning solutions tend to be brittle and prone to break. There are lots of different aspects to this, and the previous part on generalisation and re-use is one example.

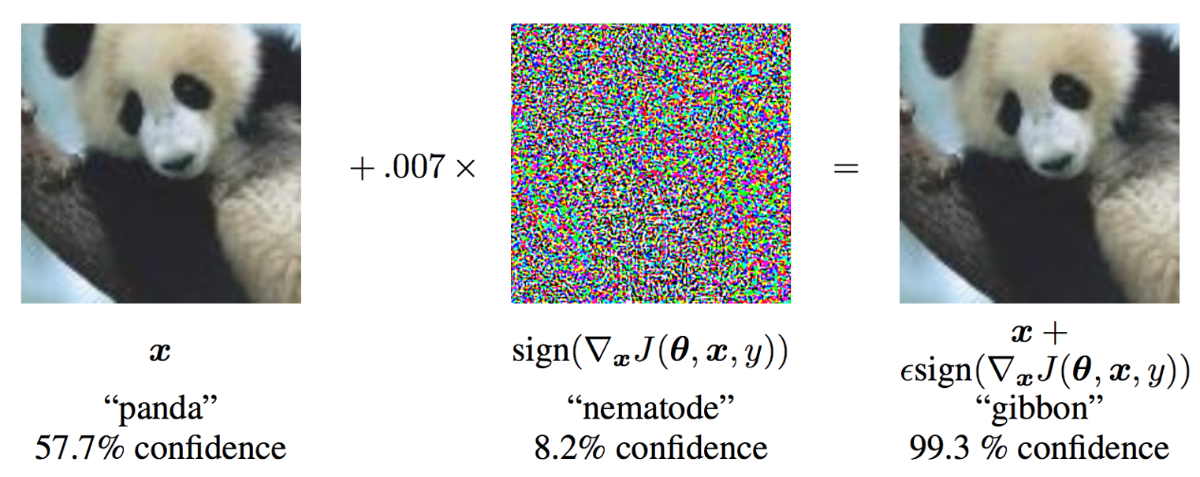

Another way of seeing it is that they are prone to manipulation, what is sometimes called an adversarial attack.

Figure 3:Example of adversarial attack Goodfellow et al., 2014.

Already this tells us that whatever this network is doing, it’s quite different to the way that humans recognise images.

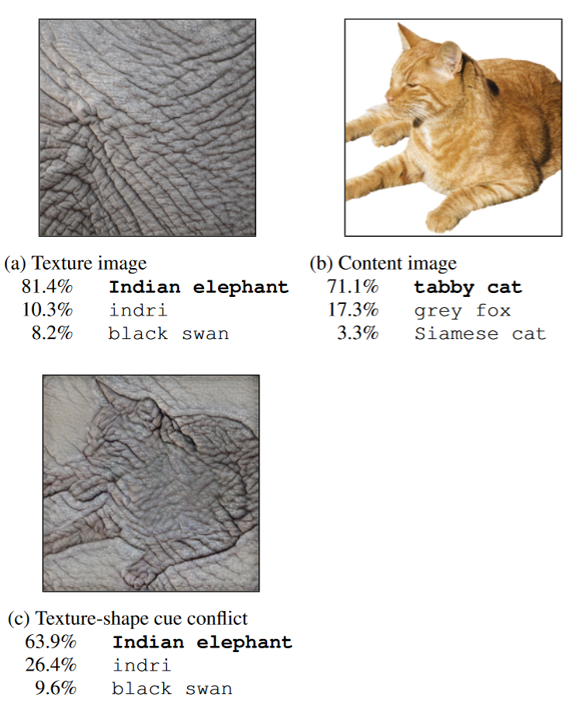

Part of the answer is known, that these networks treat texture as more important than shape, compared to humans.

Here you can see if you take a picture of a cat and give it the texture of an elephant it’s recognised as an elephant although most people would still have said cat.

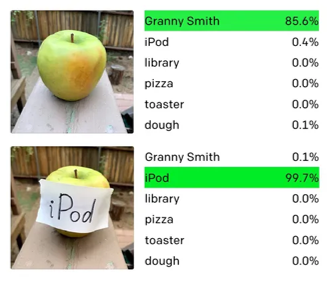

But you don’t even have to be as sophisticated as that, you can just slap on a bit of text and get it to change its mind.

These are just a few examples of what is a huge field, studying what it is that neural networks are learning, how to exploit it and how to defend against that.

Challenges for neuroscience¶

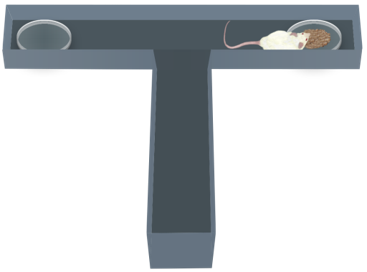

But now we want to turn away from machine learning and talk about some of the challenges for neuroscience. For the first one, you might know that scientists like to study mice running around mazes. You might imagine something like this.

Figure 6:Mouse maze experiment.

Or if you’ve been visiting the English countryside a lot, maybe this?

Figure 7:Hedge maze.

But the reality is very often more like this. In neuroscience, our experiments are usually incredible simple, often coming down to a binary choice.

Figure 8:Realistic mouse maze experiment.

There’s a good reason for that. It’s hard to train animals to do these experiments and you want an easy way to interpret the results. But it does mean that we’re studying animals to try to understand intelligent behaviour, but we’re doing it with tasks that don’t really require any intelligence.

It’s not clear that this is good enough if we really want to understand intelligence.

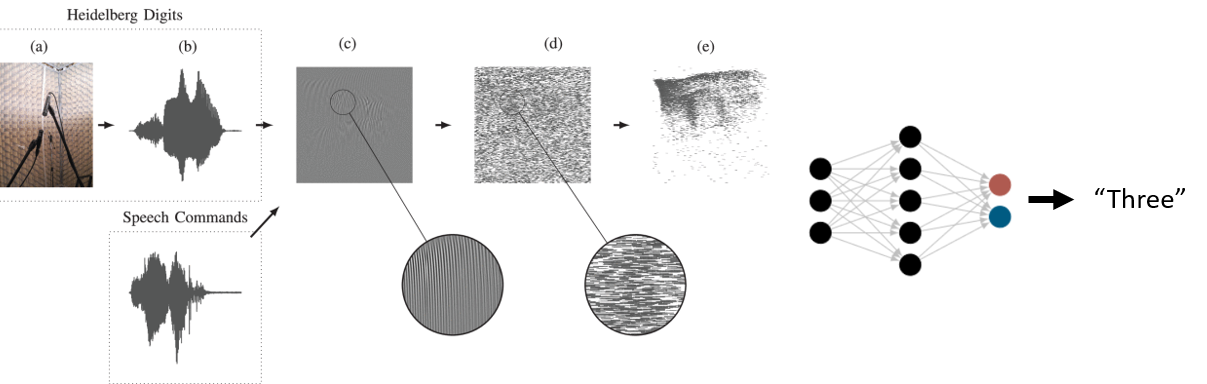

And the same is true of our models. One of the most challenging datasets for biologically realistic spiking neural networks is the Spiking Heidelberg Digits dataset, which is a database with only twenty spoken words to classify Cramer et al., 2022.

Figure 9:Spiking Heidelberg Digits dataset, from Cramer et al. (2022).

Despite that, in recent years we’ve seen a new focus in neuroscience on challenging tasks of the sort that are common in machine learning, and it has led to a huge amount of exciting new work.

Historically, neuroscience and machine learning were tightly linked and that led to some fantastic and groundbreaking work in both fields.

Our bet is we’ll make more progress in both fields if people know what’s going on in the other one.

We hope you’ll enjoy the course!

- Silver, D., Schrittwieser, J., Simonyan, K., Antonoglou, I., Huang, A., Guez, A., Hubert, T., Baker, L., Lai, M., Bolton, A., Chen, Y., Lillicrap, T., Hui, F., Sifre, L., van den Driessche, G., Graepel, T., & Hassabis, D. (2017). Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature, 550(7676), 354–359. 10.1038/nature24270

- Kansky, K., Silver, T., Mély, D. A., Eldawy, M., Lázaro-Gredilla, M., Lou, X., Dorfman, N., Sidor, S., Phoenix, S., & George, D. (2017). Schema Networks: Zero-shot Transfer with a Generative Causal Model of Intuitive Physics. arXiv. 10.48550/ARXIV.1706.04317

- Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., & Szegedy, C. (2014). Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. arXiv. 10.48550/ARXIV.1412.6572

- Geirhos, R., Rubisch, P., Michaelis, C., Bethge, M., Wichmann, F. A., & Brendel, W. (2018). ImageNet-trained CNNs are biased towards texture; increasing shape bias improves accuracy and robustness. arXiv. 10.48550/ARXIV.1811.12231

- Goh, G., Cammarata, N., Voss, C., Carter, S., Petrov, M., Schubert, L., Radford, A., & Olah, C. (2021). Multimodal Neurons in Artificial Neural Networks. Distill, 6(3). 10.23915/distill.00030