Introduction¶

This week we’re going to cover what we consider to be open issues in neuroscience.

In this section, we’re going to discuss the question “does neuroscience work and how could we know?”.

More data¶

Through most of the course, we’ve shown you how neuroscientists are collecting increasingly large datasets - of neuron morphology and activity, and we’ve discussed what we can learn from these datasets.

For example:

- Scala et al. (2023) “Phenotypic variation of transcriptomic cell types in mouse motor cortex”

- Jun et al. (2017) “Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity”

- Steinmetz et al. (2021) “Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings”

To some extent an implicit assumption behind these efforts, is that with more data will come more understanding, and that given enough data we would understand the brain.

But is that true?

Could a neuroscientist understand a microprocessor?¶

This is the question tackled by this paper entitled “Could a neuroscientist understand a microprocessor?”

Which was inspired by an earlier paper, called “Can a biologist fix a radio?”.

In Jonas & Kording (2017), the authors take an old microprocessor which runs three video games, and try to understand how it works by applying methods from neuroscience.

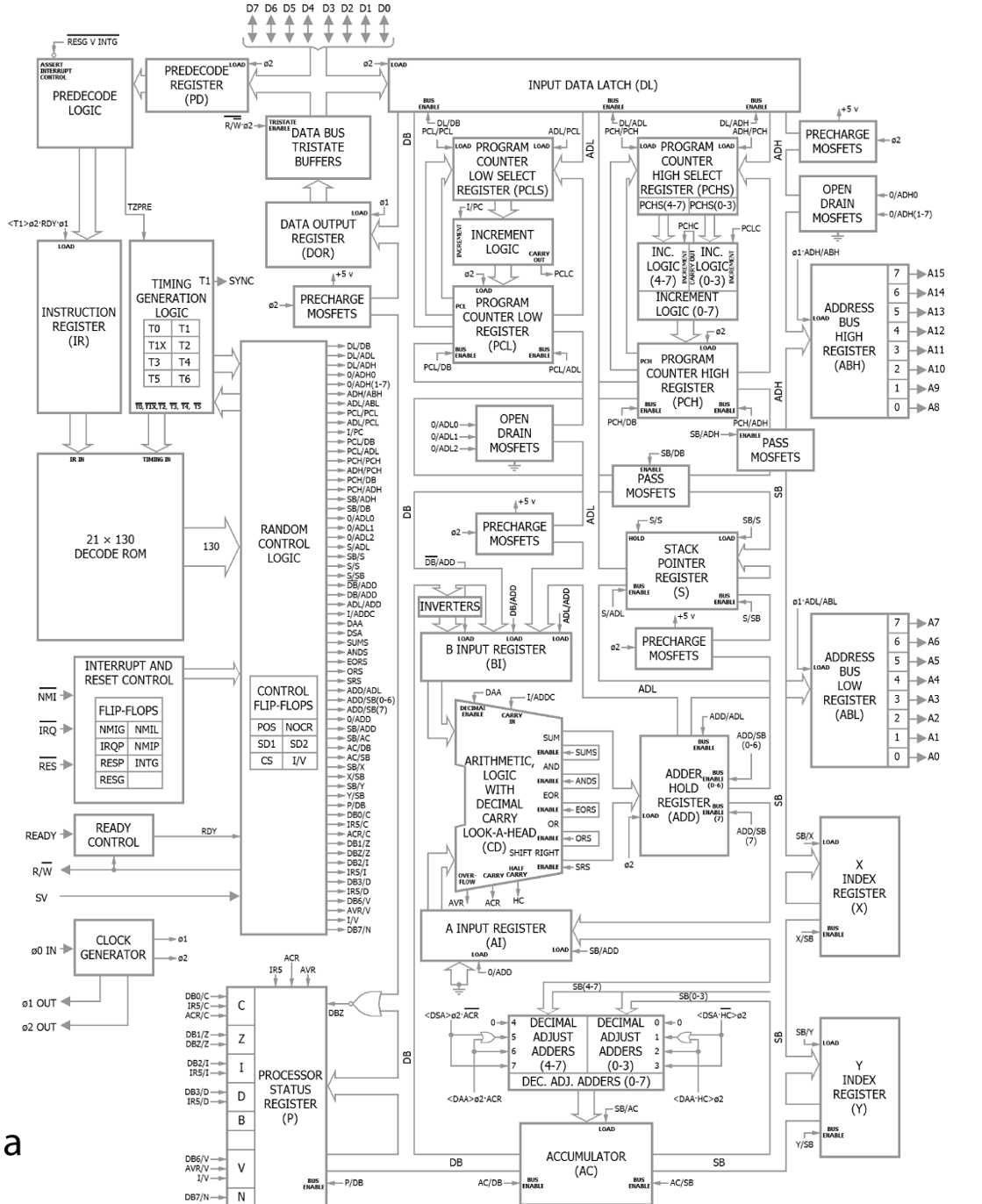

Figure 1:For an artificial system like a microprocessor, we understand how it’s hardware enables it’s function. From Jonas & Kording (2017).

Critically, we know how the microprocessor works - so we can test how well these methods do at recovering that information.

While this may seem like an odd idea, the microprocessor is in some ways not that different from the brain. For example:

- It’s transistors and their connections resemble neurons.

- And, the time-varying activity of theses transistors transforms it’s inputs to outputs.

Also, while there are many differences - like the fact the transistors are deterministic and easy to observe and manipulate, these differences should actually make the microprocessor easier to interpret than biological data.

First, the authors obtained the microprocessors connectome - i.e. a map describing how every transistor connects to every other transistor, and did some analysis of this.

While they find some interesting results, it’s difficult to see how you could go straight from a networks structure to understanding it’s function. And the authors highlight the fact that we don’t have algorithms which can do this.

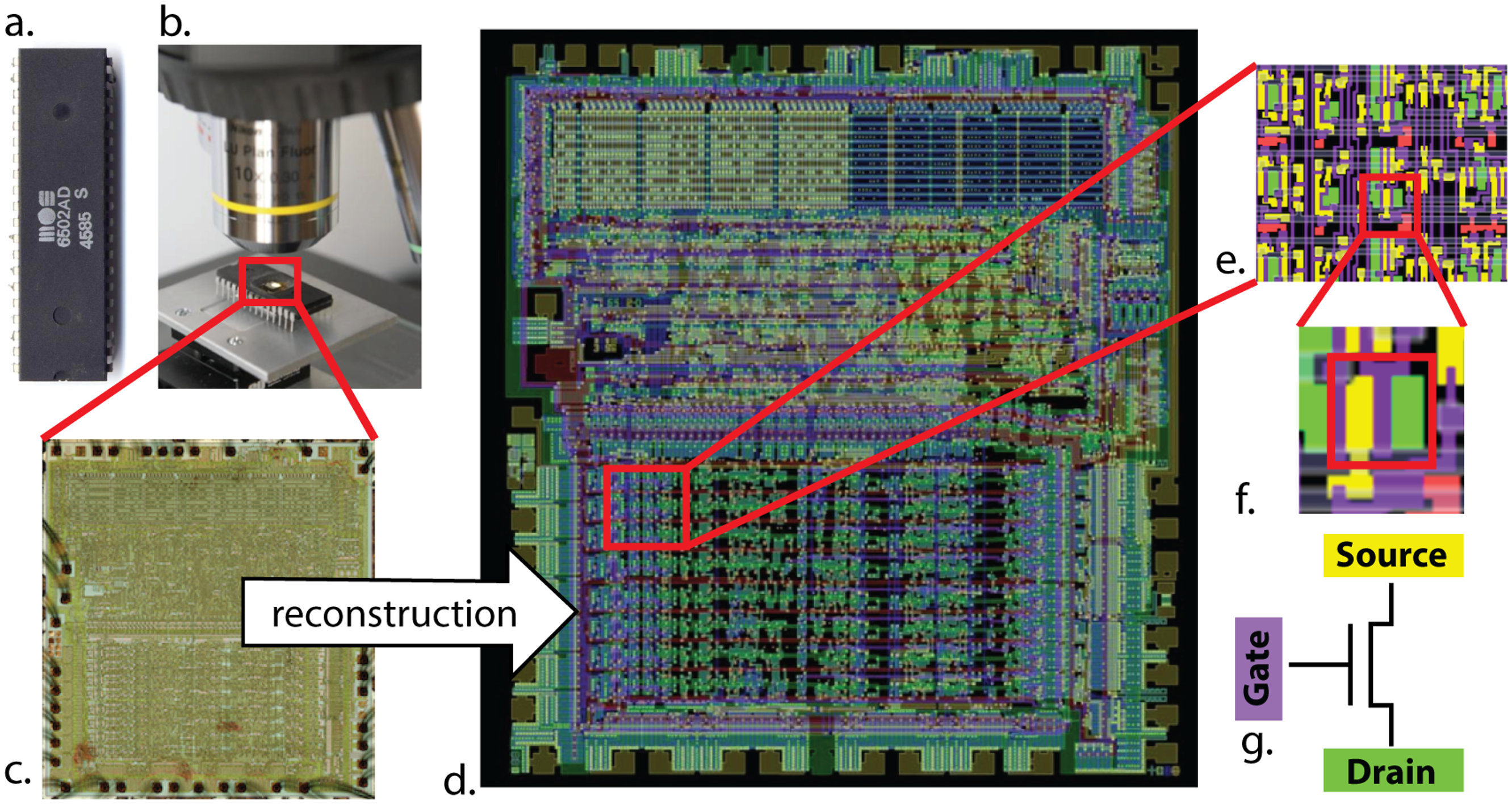

Figure 2:By combining light microscopy and computer vision algorithms, one can obtain the microprocessor’s transistor-transistor connection map (or connectome). From Jonas & Kording, 2017.

So next, they simulate the microprocessor, and observe the activity patterns of it’s transistors - much like a neuroscientist might record and analyze neural activity.

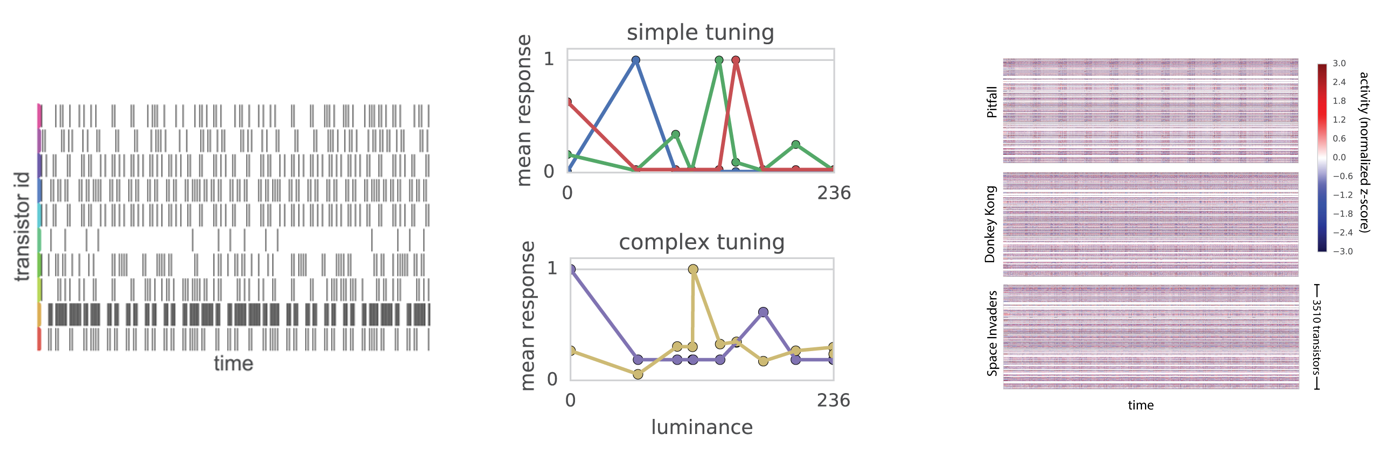

Figure 3:The microprocessor’s transistors transition between on and off states over time. When plotted (left) these resemble the spike train’s of biological neurons. From these data, one can calculate each transistor’s “tuning” to different features. For example, output pixel luminance (middle). Or, compare transistor activity across time and tasks (right). From Jonas & Kording, 2017.

The figure on the left shows the off-to-on transitions of 10 transistors over time (which look surprisingly like spikes in a raster plot).

With these data, the authors then try to analyse the tuning properties of individual transistors. In this case, how their activity changes as a function of pixel luminance. The middle plot shows some of the results from this analysis - with:

- Luminance on the x-axis

- The transistors’ mean response on the y-axis

- Different coloured lines representing 5 different transistors.

Like neurons in the brain, some transistors seem to have simple tuning and are correlated with single luminance values. While others, seem to have more complex tuning.

So does this help us to understand how the microprocessor works?

Not really, as in truth, none of these transistors directly controls pixel luminance.

So maybe, instead of analysing individual transistors we should try to identify functional ensembles - groups of transistors with correlated temporal dynamics?

To do that the authors, record the activity of all 3,510 transistors simultaneously over time - during the three different video games. The data is shown in the rightmost plot, with time on the x-axis and transistors on the y-axis per game, and again you can see that it resembles large-scale neural data.

They then analyze this with non-negative matrix factorization. This time they find, dynamics which match features of the microprocessor like the clock and read-write signal.

But again, this falls short of providing us with some substantial understanding of how the microprocessor works.

So what if instead of just observing the system we tried to manipulate it?

To do that the authors silence each transistor in turn, and check if each of the 3 video games will boot or not.

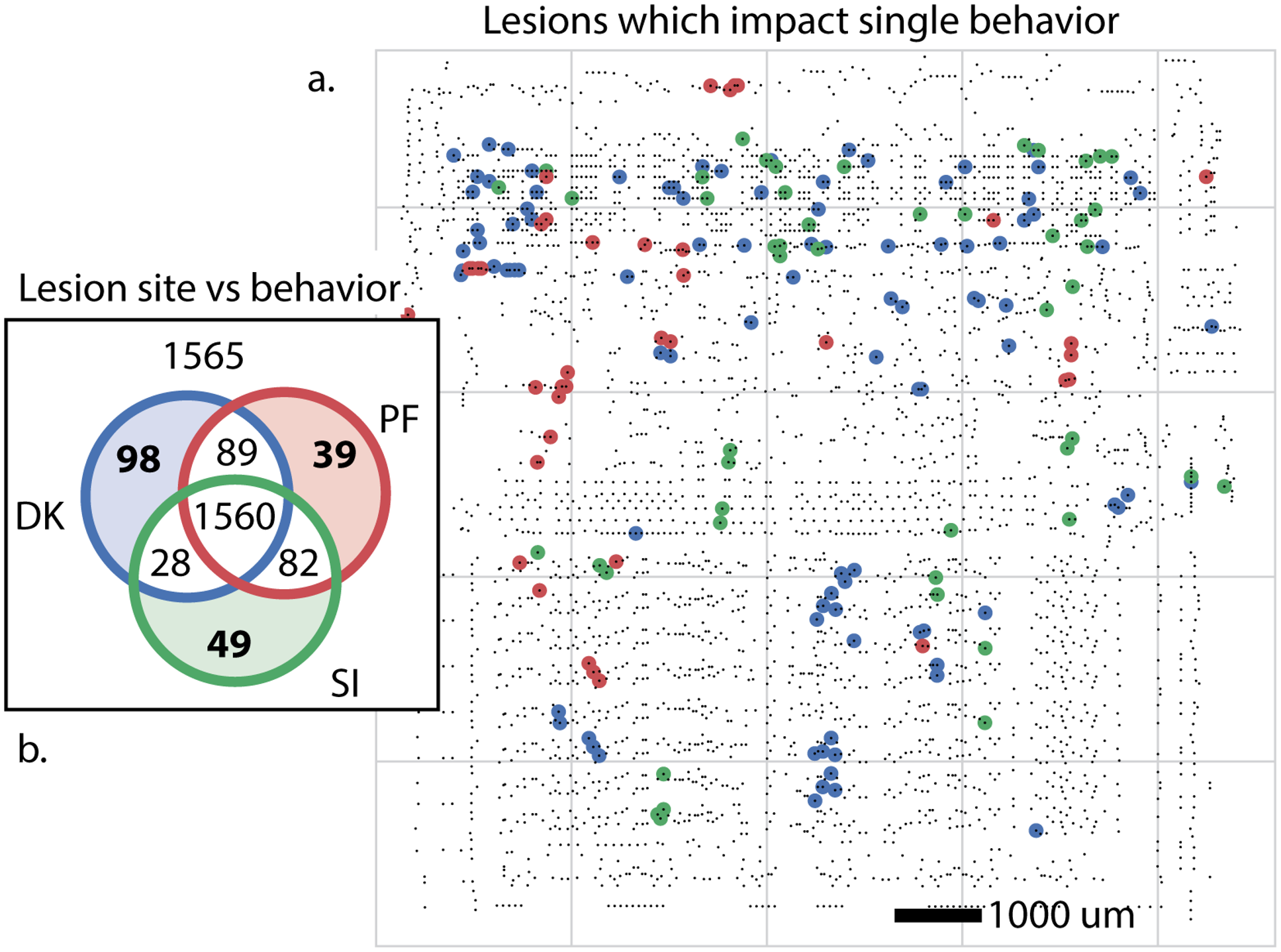

Figure 4:By silencing (lesioning) each transistor in turn it is possible to identify transistors which are critical for a specific behaviour (here booting one of three video games). From Jonas & Kording, 2017.

As the left of the figure shows:

- Removing 1565 of the transistors had no impact.

- Removing 1560 of them stopped the microprocessor from booting any games.

- And then small subsets of the transistors prevented one or two games from booting. The locations of the transistors which were specific to one game are mapped onto the chip on the right of the diagram.

It’s tempting to label these transistors as “Donkey Kong” or “Space Invaders” transistors - much like we may label a neuron as being visual or auditory.

But this is misleading here, as the transistors are not specific to single games, and instead implement simple functions (like full adders) which may be involved in other games we haven’t considered or even these games if we looked beyond booting.

So what would work?

What would work?¶

One suggestion from the authors is that they could have better designed their experiments to isolate individual behaviors or computations. For example, if you just recorded and manipulated the transistors while the player tried to move left - you could try to figure out how the microprocessor transforms a left controller input into a leftward movement on screen.

Another suggestion is that better methods could help. For example, in week 6 we covered why multi-element lesions may be more informative than single-element lesions.

But really how to understand complex networks is an open issue in neuroscience.

So does neuroscience work? Jonas & Kording (2017) suggests that our current approaches may not. So we need better methods and we need ground truth systems in which we can validate these.

- Scala, F., Kobak, D., Bernabucci, M., Bernaerts, Y., Cadwell, C. R., Castro, J. R., Hartmanis, L., Jiang, X., Laturnus, S., Miranda, E., Mulherkar, S., Tan, Z. H., Yao, Z., Zeng, H., Sandberg, R., Berens, P., & Tolias, A. S. (2020). Phenotypic variation of transcriptomic cell types in mouse motor cortex. Nature, 598(7879), 144–150. 10.1038/s41586-020-2907-3

- Jun, J. J., Steinmetz, N. A., Siegle, J. H., Denman, D. J., Bauza, M., Barbarits, B., Lee, A. K., Anastassiou, C. A., Andrei, A., Aydın, Ç., Barbic, M., Blanche, T. J., Bonin, V., Couto, J., Dutta, B., Gratiy, S. L., Gutnisky, D. A., Häusser, M., Karsh, B., … Harris, T. D. (2017). Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature, 551(7679), 232–236. 10.1038/nature24636

- Steinmetz, N. A., Aydin, C., Lebedeva, A., Okun, M., Pachitariu, M., Bauza, M., Beau, M., Bhagat, J., Böhm, C., Broux, M., Chen, S., Colonell, J., Gardner, R. J., Karsh, B., Kloosterman, F., Kostadinov, D., Mora-Lopez, C., O’Callaghan, J., Park, J., … Harris, T. D. (2021). Neuropixels 2.0: A miniaturized high-density probe for stable, long-term brain recordings. Science, 372(6539). 10.1126/science.abf4588

- Jonas, E., & Kording, K. P. (2017). Could a Neuroscientist Understand a Microprocessor? PLOS Computational Biology, 13(1), e1005268. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005268

- Lazebnik, Y. (2002). Can a biologist fix a radio?—Or, what I learned while studying apoptosis. Cancer Cell, 2(3), 179–182. 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00133-2