Introduction¶

One of the most surprising things in neuroscience is that there is this extraordinary method that neurons use to communicate and compute, the discrete action potential, or spike, but we don’t know why the brain does this. At a philosophical level, this might be a question without an answer: it just does because that’s the path evolution took and it could have taken a different one. That might be true, but we don’t know that for sure either. So let’s look at some of the ideas in the debate about this.

Power and reliability¶

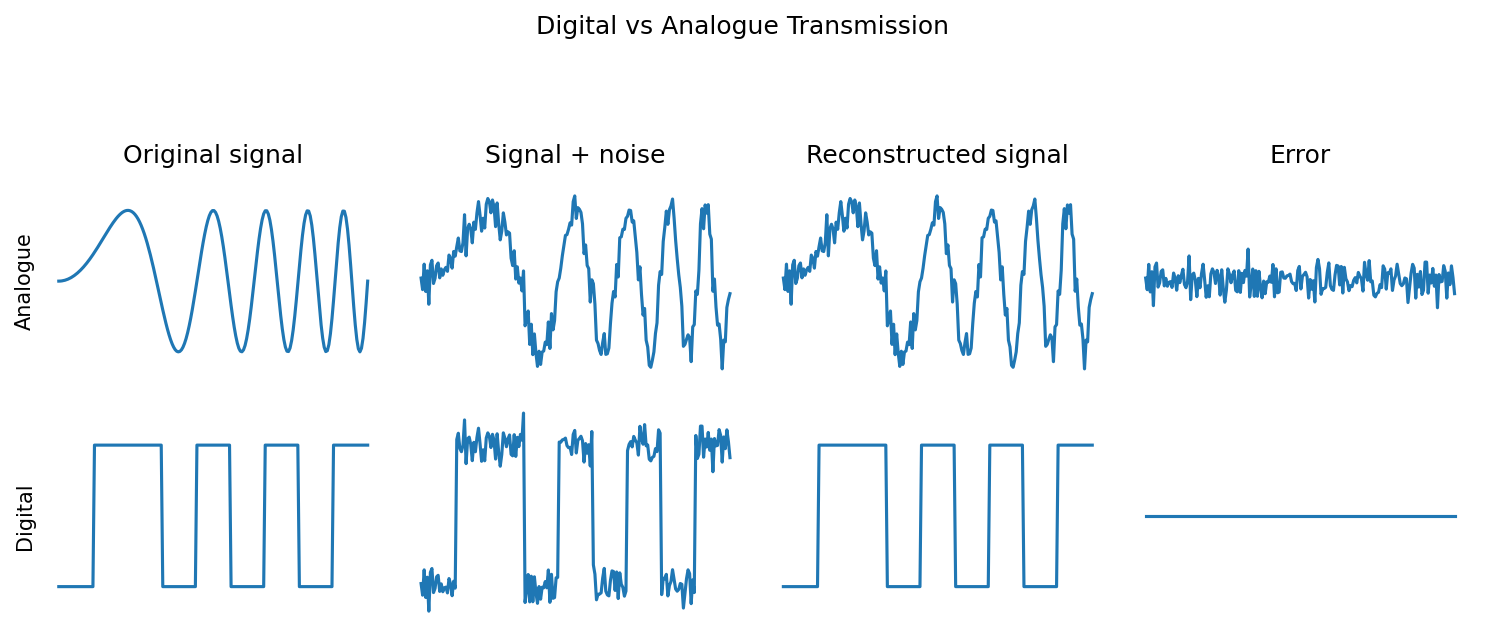

The first argument is that the main function of spikes is just that they are an energy efficient mechanism for reliably sending signals along a long wire.

This is basically the reason why digital is often preferred to analogue in communications and computing. You can reconstruct a digital signal perfectly even in somewhat noisy conditions, but noise will always degrade an analogue signal.

It’s a very valid argument and it’s likely to be part of the reason. It’s certainly a key inspiration for the neuromorphic devices we talked about last week. But, how valid is it when we know that there are many other sources of noise in the brain, like synaptic failures. And, even if it’s true, is there more than that? Do we need to understand spikes to understand what the brain is doing?

The core argument¶

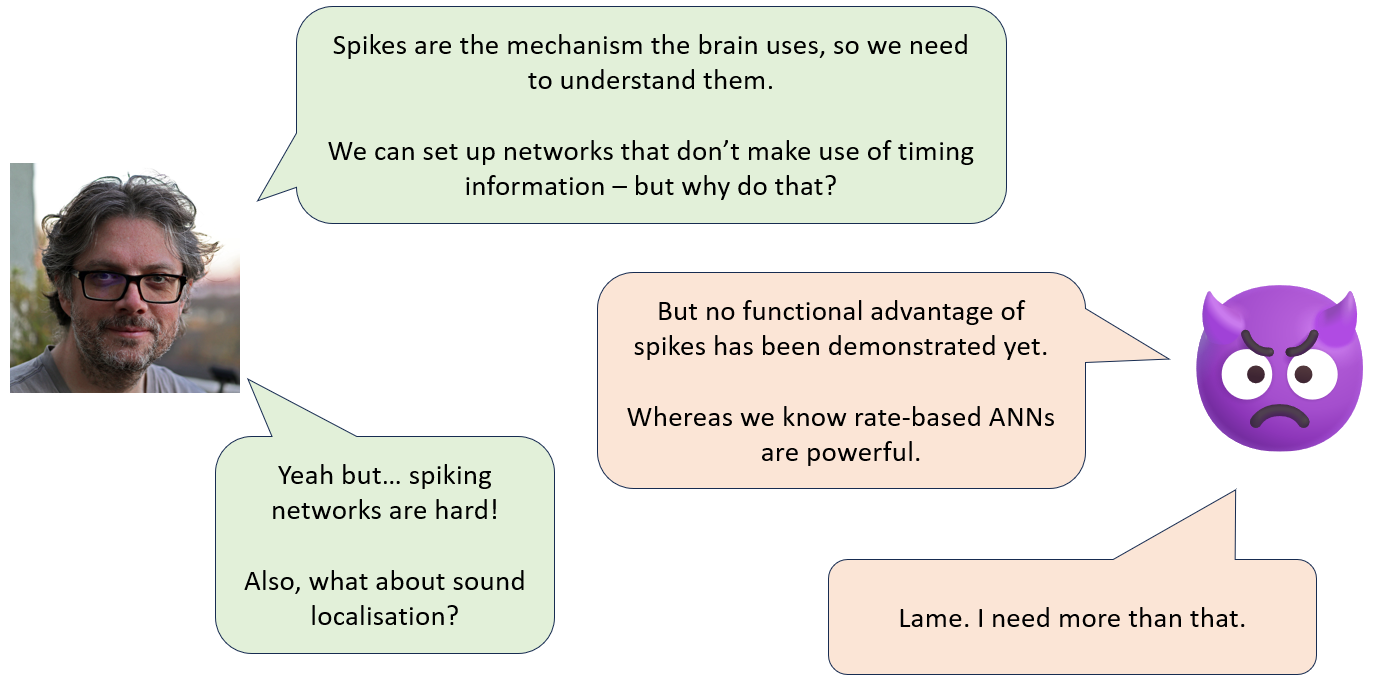

Dan’s point of view is that we know that the brain does use spikes, and so we need to understand them if we want to understand the brain.

Even if we think that the brain only uses spikes for their rates, we have to understand how the brain could discard the non-rate information in spike trains. People have worked on that, showing how you can set up spiking neural networks so that they behave as if they were just conveying rates. But, why would the brain actively throw away a potentially useful sort of computational richness? Dan’s take is that if you want to say that the brain only uses rates, it’s on you to show that using spike timing is actively harmful in some way so that it’s worth the effort to discard that information.

But there’s a counter argument to that, which we’re representing here by this totally neutral choice of emoji. If spike times are carrying all this potentially useful information and rich dynamical behaviour useful for computation, how come we’ve never managed to demonstrate a case where spiking performs better than non-spiking?

We know that rate-based artificial neural networks are powerful, but we can’t yet say the same about models of spiking neural networks. You’ve seen in previous weeks that training spiking neural networks is making great strides, but we’re still far from the levels of performance of ANNs.

While Dan thinks this is clearly true, part of the reason for that is that we have good theory and techniques for working with continuous and differentiable systems, and not as good yet for hybrid discrete and continuous systems. That’s a limitation on our mathematical techniques, but there’s no reason the biological mechanisms of the brain should have the same constraints.

Also, it’s not entirely true. We do know some systems where precise spike times are definitely important - like the sound localisation circuit.

Still though, Dan does recognise that just saying it’s hard and giving one example is not a particularly convincing argument. A big part of Dan’s research is about trying to do this better.

Is it even a real argument?¶

Before we get further into the arguments, it’s worth asking if the reason we haven’t made progress on the issue is that there’s no actual issue.

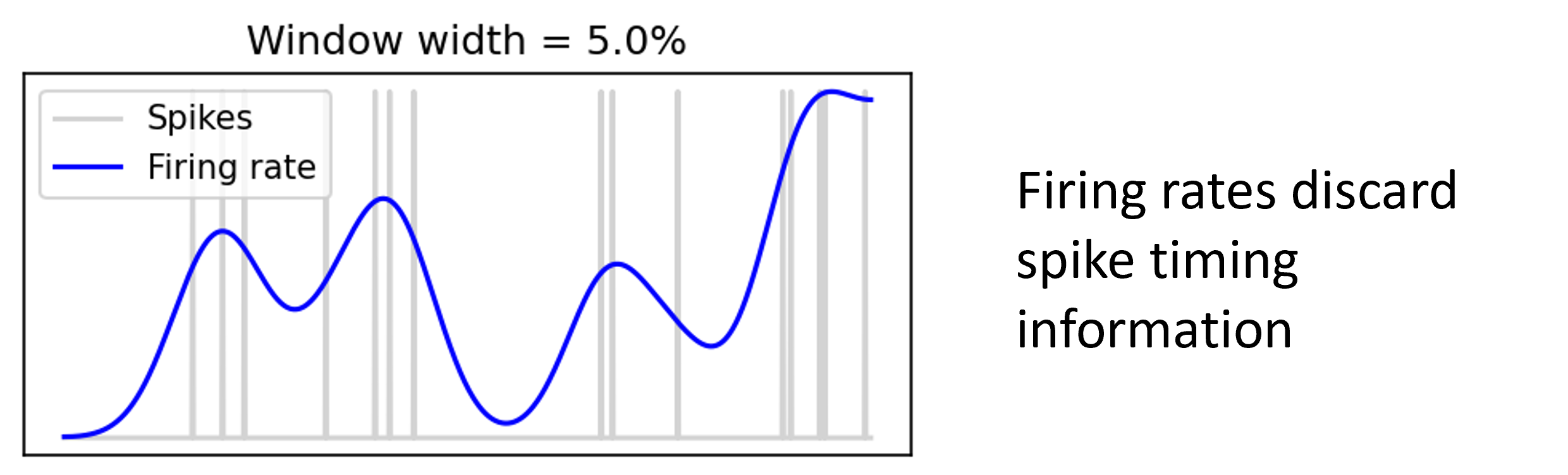

If we smooth out spike times as a sort of proxy of firing rate, we can see that indeed it’s not capturing the structure of the spike times. This is the picture people usually have in mind.

Figure 2:Time varying firing rate with window width 5%.

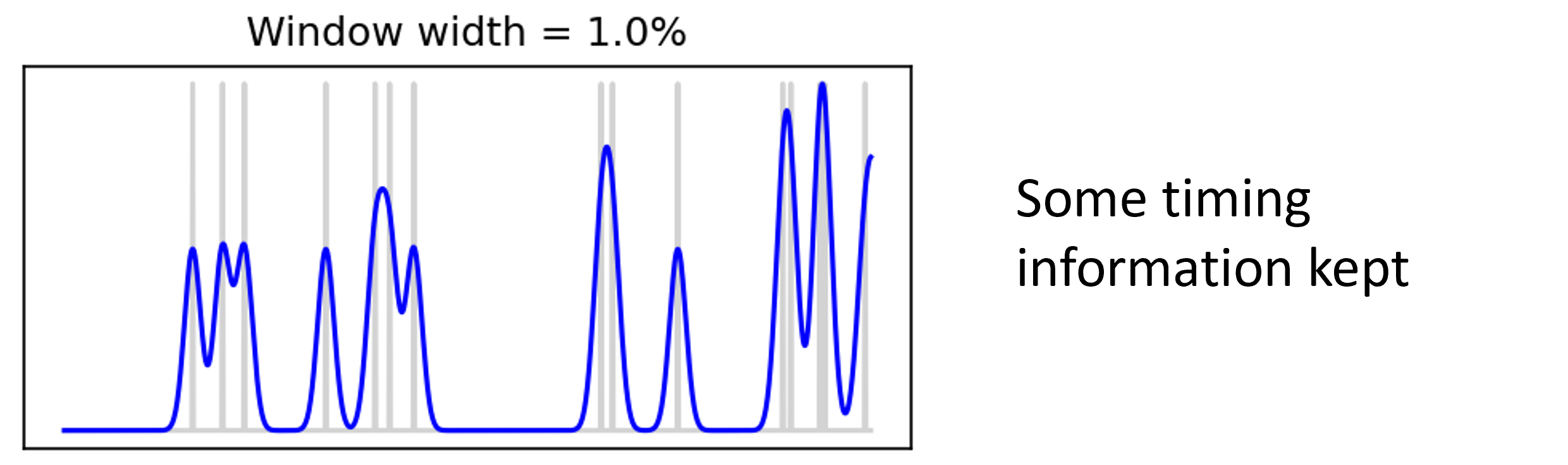

But if we use a narrower window, that becomes less obvious.

Figure 3:Time varying firing rate with window width 1%.

Until eventually there’s no distinction between firing rates and firing times.

Figure 4:Time varying firing rate with window width 0.1%.

So does this mean that we can just ignore the distinction between spike times and firing rates?

Not quite.

Firstly, while spikes can tell you everything you need to know about firing rate at any time scale, the reverse isn’t true. Only the narrow smoothing windows tell you about the spike times.

Secondly, the argument is not just that the concept of rates can do anything that times can do, but that spikes are actually generated by a process where spike timing is not important. This is a much stronger statement.

On the face of it, it’s surprising. We know that single neurons don’t discard spike timing information from their inputs, and that they produce reliable spike times in response to a time varying input current. It is possible to set up a network of neurons that discards the timing information, but as we said before, this seems like a strange and unnecessary thing to do. Of course, that doesn’t mean that’s not what the brain does - it is often surprising!

So what can we conclude?

Well, it’s not quite as simple as saying that firing rates and spike times are mathematically the same thing, but it is a useful point of view to keep in mind in this debate.

Information theoretic view¶

Let’s return to the point that knowing the spike times tells you everything there is to know about spike rates, but not necessarily vice versa. Can we quantify that? It’s not entirely straightforward, but people have tried using information theoretic approaches.

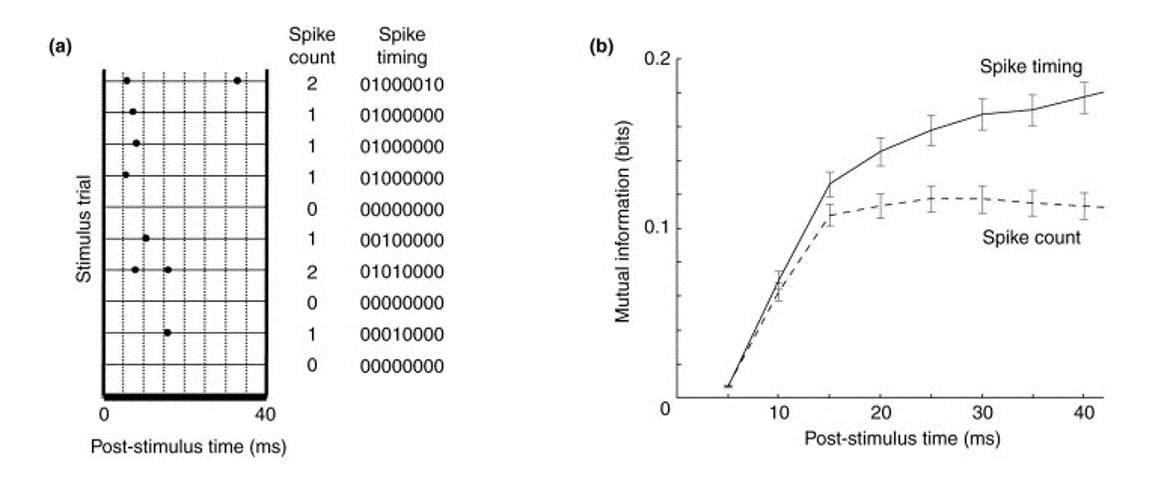

The idea is to record some sensory information - in this case the amount that the rat’s whiskers have been deflected - and simultaneously record the activity of a set of neurons. Then you ask, how much information in bits does knowing the spike train tell me about the amount the whiskers have been deflected?

Figure 5:Mutual information between spike trains and whisker movements.

You then do this using either the full set of spike times, or just the spike rates - or counts in this figure. Of course, since the timing information tells you the rates or counts, the amount of information must be at least as large, but the finding here is that it’s much larger. Knowing the spike times tells you almost twice as much as knowing the counts alone. And this is a finding that has been found many times in different sensory modalities and different species.

Figure 6:Information contained in spike rates versus spike timing.

At first this looks like a knock down argument in favour of spike timing, but it’s not quite as clear cut as that:

Firstly, it’s really hard to measure mutual information in these very high dimensional settings and so it’s hard to be 100% confident that what we’ve done is meaningful.

Secondly, just because the information is there doesn’t mean that the animal makes use of that information.

Spike times not reproducible¶

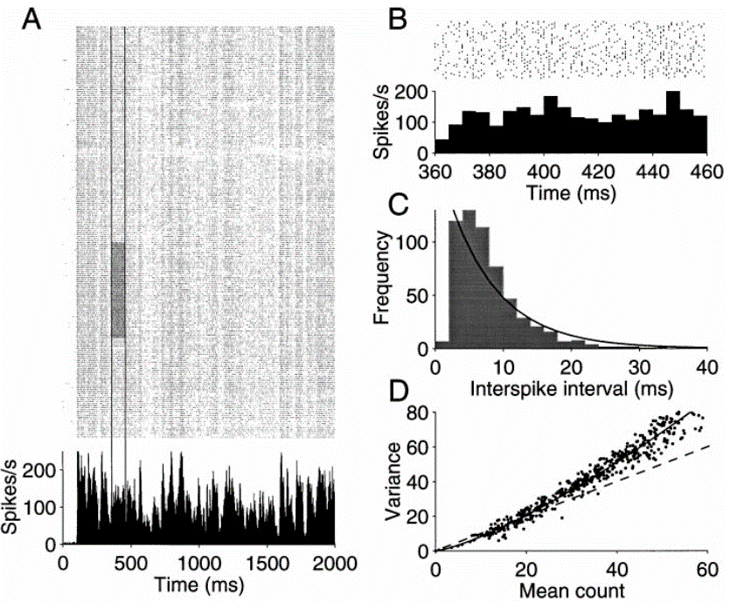

Another argument against spike times being important is that they are often not reproducible and so they couldn’t be used as the basis of a neural code.

We’ve seen before the result that if you inject a time varying current into a neuron you get reproducible spike times.

But by contrast if you repeatedly show an animal the same stimulus you often get spike times that are very different. Spike counts are also highly variable, but the argument is that these differences can be averaged out across the population.

Figure 7:Spike timing is not reproducible across trials Shadlen & Newsome, 1998.

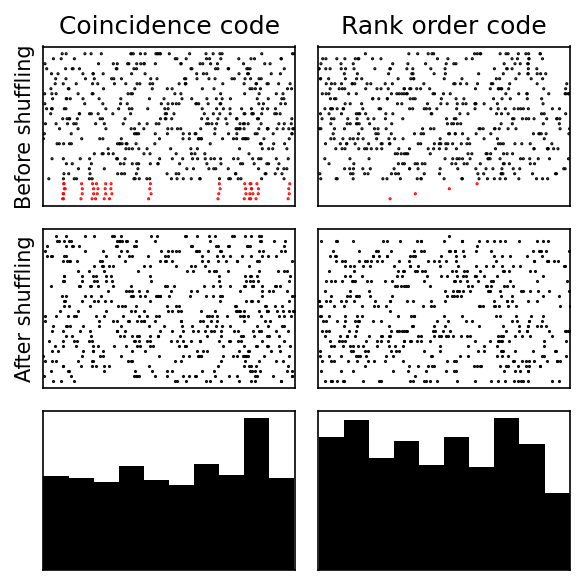

However, you wouldn’t necessarily see obviously reproducible spike timing patterns. Here are two spike timing codes that give rise to histograms that are indistinguishable at a glance from one with no meaningful spike times. On the top row you see the spikes ordered so that four of the neurons have a special relationship to each other in terms of their timing. On the left they all have the same time plus or minus a bit of noise. On the right that are in a fixed order relative to each other. However, if you randomly shuffle the order that you plot them or compute the histogram of spike times, you don’t see anything resembling a spike timing code.

A rank order code is a bit tricky to work with and implies a lot of constraints on the network structure, but a coincidence code is quite natural, which brings us to the next argument.

Correlations¶

The next argument is that if coincidence were an important part of the neural code, we would expect to see high pairwise correlations between neurons’ spike trains, which we don’t see in recordings. It’s true that we would expect to see correlations, but it’s a surprising fact that a spike timing code doesn’t need them to be high. In fact, input correlations that are so small as to be indistinguishable from noise can have a huge effect on downstream neural firing.

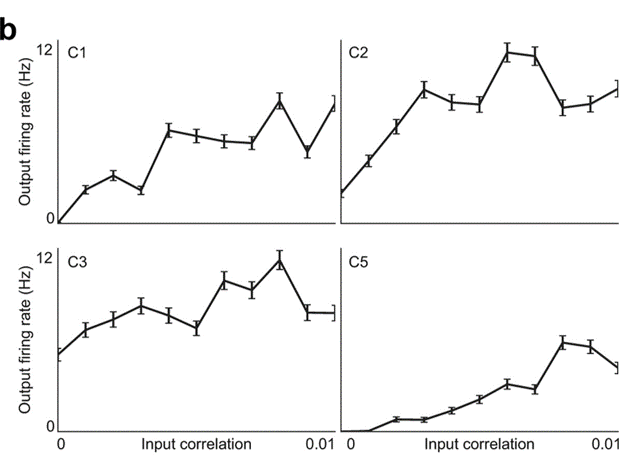

Rossant et al. (2011) generated simulated input spike trains with pairwise correlations varying from 0 to 0.01, injected those spikes as input currents into cortical neurons, and then measured the output neuron firing rate. As you can see, the neurons were incredibly sensitive to even these tiny differences in correlation. In the case of neuron C1 its firing rate increased from zero to almost 10 spikes per second.

Figure 8:Output firing rate is sensitive to tiny correlations in real neurnons Rossant et al., 2011.

They also checked that the same thing can be seen in a leaky integrate-and-fire neuron.

Figure 9:Output firing rate is sensitive to tiny correlations in simulated neurons Rossant et al., 2011.

So the fact that we don’t see huge correlations in spike trains doesn’t mean that timing information isn’t critical to network functioning. In fact, we can go further than this. You can argue that regardless of whether or not the code is timing or rate based, you’d expect to see low correlations and individual spike train statistics consistent with them being generated by a Poisson process that has no meaningful timing information.

These statistics are what you’d get in any scenario when each individual spike carries the maximal amount of information.

For more

This has been developed into an interested and detailed theory by Sophie Deneve:

Can we settle this?¶

There’s more to these arguments than this little sketch of course, but you can begin to see the problem. It’s a debate that’s been going for decades and doesn’t seem any closer to being resolved. So what would it take?

Well, we can’t decide purely based on computational abilities. We’ve seen that spiking neural networks are universal function approximators, and so are rate-based artificial neural networks.

We could try manipulating circuits in a way that disrupts spike timing but not rate to see if it changed the function of the network. We can do that for single neurons but for population-based spiking networks, that experiment is beyond our capabilities for the moment.

One approach that we’re looking into is trying to show that spikes let you do more with fewer neurons and synapses. This would mean reduced energy and space requirements, both of which are critical for biological networks. It’s not yet clear if this is true, but we’ve seen some suggestive signs in our research.

Finally, maybe spiking neural networks need less training data. This would be a dramatic difference. Is it likely? It’s possible that somehow temporal sparsity or thresholding will be important for that, but we haven’t seen anything that convinced us of this yet.

If we had to guess right now we’d say the most likely is that the brain primarily uses spiking to reduce resources, both energy and space, and that the optimal way to learn with minimal data will turn out to be neither spikes nor rates, but something we haven’t imagined yet. Maybe one of you will discover it?

- Shadlen, M. N., & Newsome, W. T. (1998). The Variable Discharge of Cortical Neurons: Implications for Connectivity, Computation, and Information Coding. The Journal of Neuroscience, 18(10), 3870–3896. 10.1523/jneurosci.18-10-03870.1998

- Rossant, C., Leijon, S., Magnusson, A. K., & Brette, R. (2011). Sensitivity of Noisy Neurons to Coincident Inputs. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(47), 17193–17206. 10.1523/jneurosci.2482-11.2011

- Deneve, S. (2008). Bayesian Spiking Neurons I: Inference. Neural Computation, 20(1), 91–117. 10.1162/neco.2008.20.1.91