Introduction¶

In the last two sections we’ve looked at how we can record and analyze neural activity.

But, to some extent these methods simply correlate neural activity with different variables, and we can’t really be sure that our findings are casually relevant.

In other words, once we’ve found neurons that respond to a stimulus or precede a behavior, we would like to know if disrupting those neurons would have any effect on the animal’s ability to respond to that stimulus or implement that behavior.

We can do this by manipulating neural activity, and these manipulations can be either irreversible or reversible.

Irreversible¶

In humans, irreversible changes usually result from accidents, disease processes or surgical interventions. For example, earlier in the course we mentioned a paper which used fMRI to study two patients with damage to their corpus callosums.

But in animal models, we can irreversibly destroy single neurons or even whole parts of the brain, to study the effect.

For example, Lopes et al. (2023) used rats to study the role of motor cortex: a part of the brain where many studies have observed neural activity correlated with movement.

In this paper, the authors:

- Took a group of rats, destroyed or lesioned motor cortex in half of the animals, and left the other half as controls (with no motor cortex damage).

- They then trained all of the rats to cross the steps shown here.

The video shows one animal with a motor cortex lesion learning the task (lesion A), and then one control animal. Hopefully, you can see how similar the two animals movement patterns are. And surprisingly, the authors found no differences between the two groups.

Figure 1:Rats with motor cortex lesions cross a series of steps similarly to controls Lopes et al., 2023.

One conclusion from this result could be that motor cortex isn’t needed for a simple task like this. So, the authors then increased the difficulty of the task by making more and more of the steps unstable.

Surprisingly, again they didn’t see any difference between the two groups. Until they looked at their data very carefully.

What they found was that when the animals first encountered the unstable steps, they responded in one of the three ways shown in this video:

- Some controls stopped to investigate the unstable step.

- Some controls compensated by adjusting their movement.

- But the animals with motor cortex lesions stopped moving for several seconds.

This suggests that the main role of this brain area may be to help the animal to adapt its behaviour to unexpected situations.

Though, in the context of this video, I think this paper nicely illustrates that while we may assign roles to neurons or brain areas based on observing their activity, we can only really confirm or refute their roles by manipulating them.

Figure 2:Rats with motor cortex lesions respond differently to unstable steps / unpredictable situations Lopes et al., 2023.

However, we don’t always have to use irreversible manipulations, as there are reversible methods too.

Reversible¶

In humans, one approach is called trans-cranial magnetic stimulation or TMS, which uses magnetic fields to alter the activity of brain regions. But, in animal models we can control neural activity more precisely and one great method for doing this is optogenetics: which uses light-gated proteins to control neural activity. Some of these light-gated proteins are genetically engineered, but some occur naturally in things like algae.

For example:

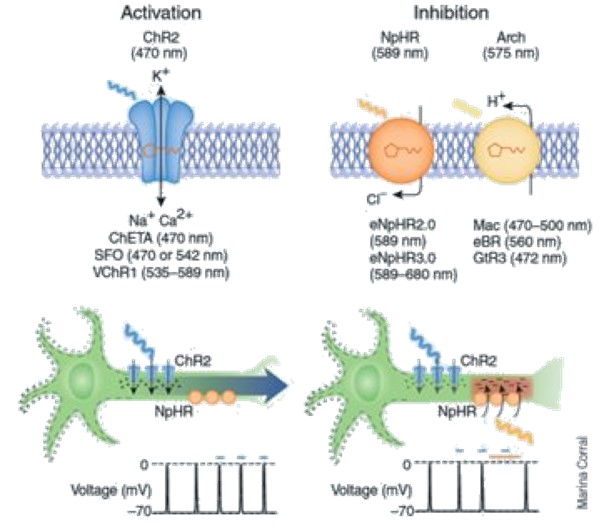

- Channelrhodopsin - shown on the left of this figure. Is an ion channel which, when exposed to blue light, changes its structure and allows positive ions to flow into neurons, increasing their membrane potential and spiking activity.

- In contrast, the proteins shown on the right [Halorhodopsin and Archaerhodopsin] respond to yellow light by either moving chloride ions into the neuron or moving hydrogen ions out, both of which will decrease the neurons membrane potential and spiking activity.

So, by expressing these channels in neurons and then triggering them with light we can study neurons roles by reversibly activating or silencing them.

Figure 3:Diagram showing how optogenetic tools can be used to activate (left) or inhibit (right) neurons Pastrana, 2010.

While, this may seem a bit detached from machine learning, we can actually use the same types of manipulations to interrogate artificial neural networks.

Single-element lesions in ANNs¶

For example, in Fakhar & Hilgetag (2022) the authors studied an ANN by lesioning it extensively. To create their ANN, they used an evolutionary algorithm called (NEAT) to evolve a neural network which could play the arcade game Space Invaders.

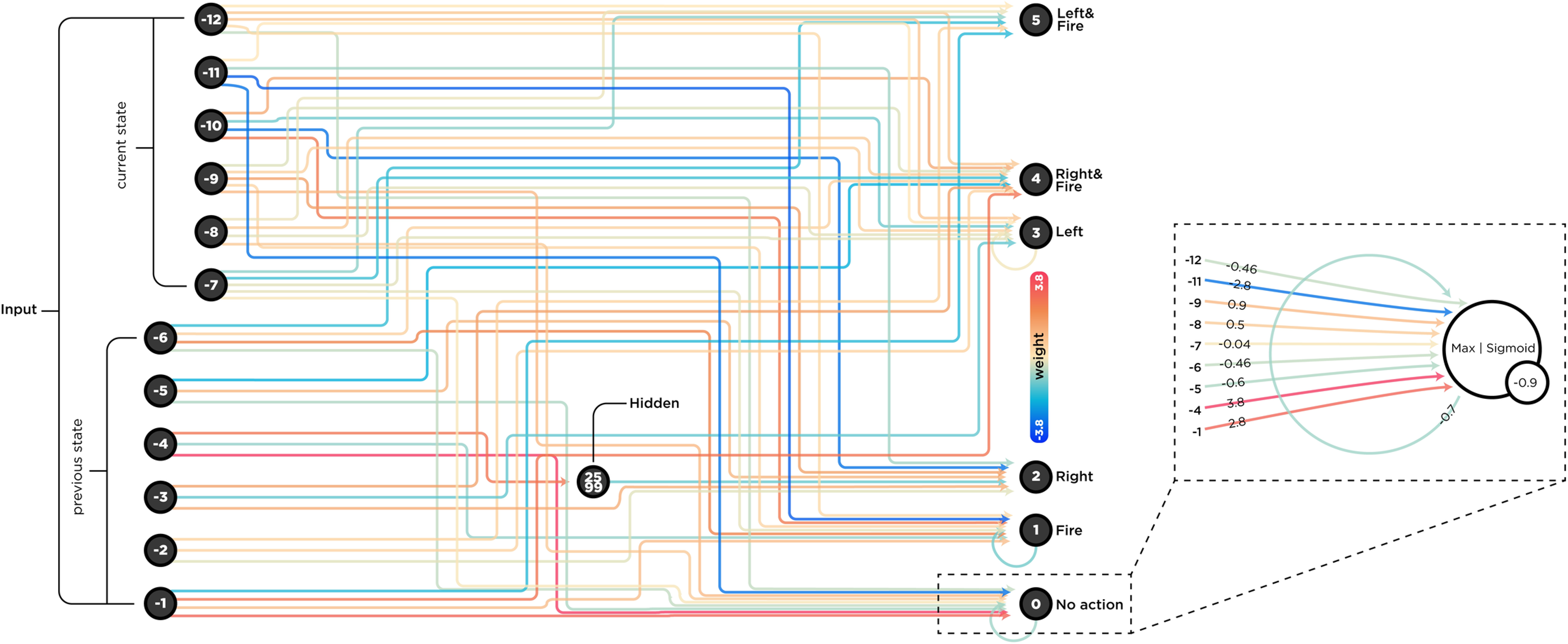

Their evolved network is shown here:

- On the left are the networks 12 input nodes - which receive a compressed version of the video game.

- On the right are the networks 6 output nodes - which encode actions like move left, move right, and fire.

- And then in between is a single hidden node and many connections whose weights are color-coded.

Figure 4:A neural network evolved to play space invaders Fakhar & Hilgetag, 2022.

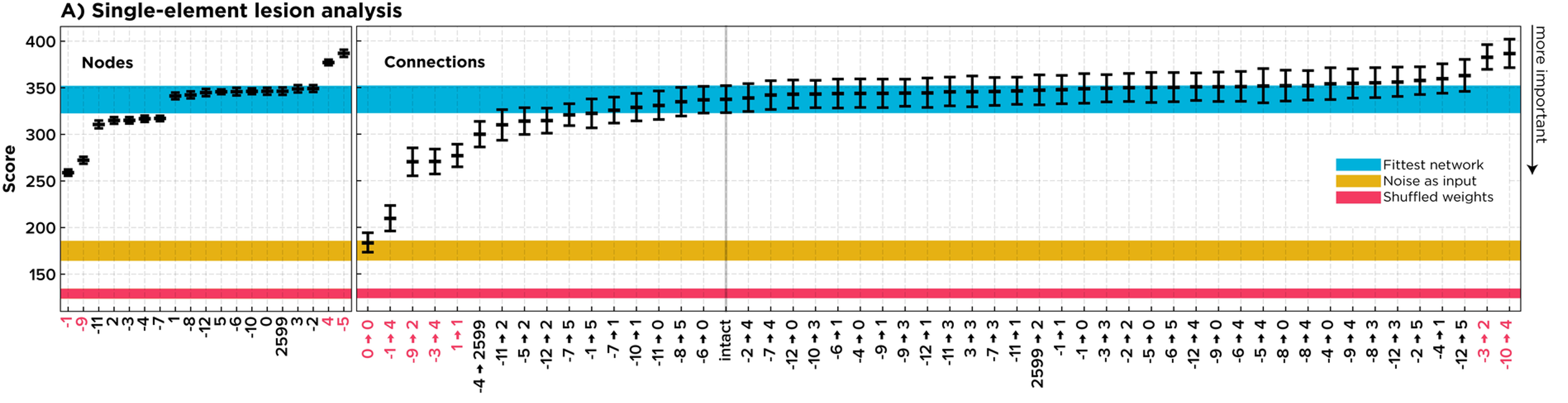

To manipulate their network they then silenced each node one-by-one and checked how well the network performed with each node silenced individually. This figure shows their results: the y-axis shows the networks score - with higher being better. For comparison, the blue stripe shows the networks normal performance, and the red stripe shows it’s performance if you shuffle its weights.

On the left of the figure, each point on the x-axis corresponds to silencing a single node, and you can see that ablating different nodes leads to different scores - which implies that some nodes are more important for the task than others. And interestingly you can also see that ablating two of the nodes, increases the networks score; suggesting they hinder the network.

On the right of the figure, the authors also silence every weight in turn and study the effect on performance, and interestingly their results suggest that many weights could be removed without much effect.

Figure 5:How silencing the individual nodes (left) or weights (right) alters the performance of a trained neural network Fakhar & Hilgetag, 2022.

However, the results from single-element manipulations like these could be misleading. For example, imagine if two units in this network perform the same function in parallel. Then silencing either one alone, may not result in a change to the networks score and we could wrongly conclude that neither of these units are important.

Taking this further, because of the complex interactions between elements in a network (either artificial or biological), there are likely many variants of this problem.

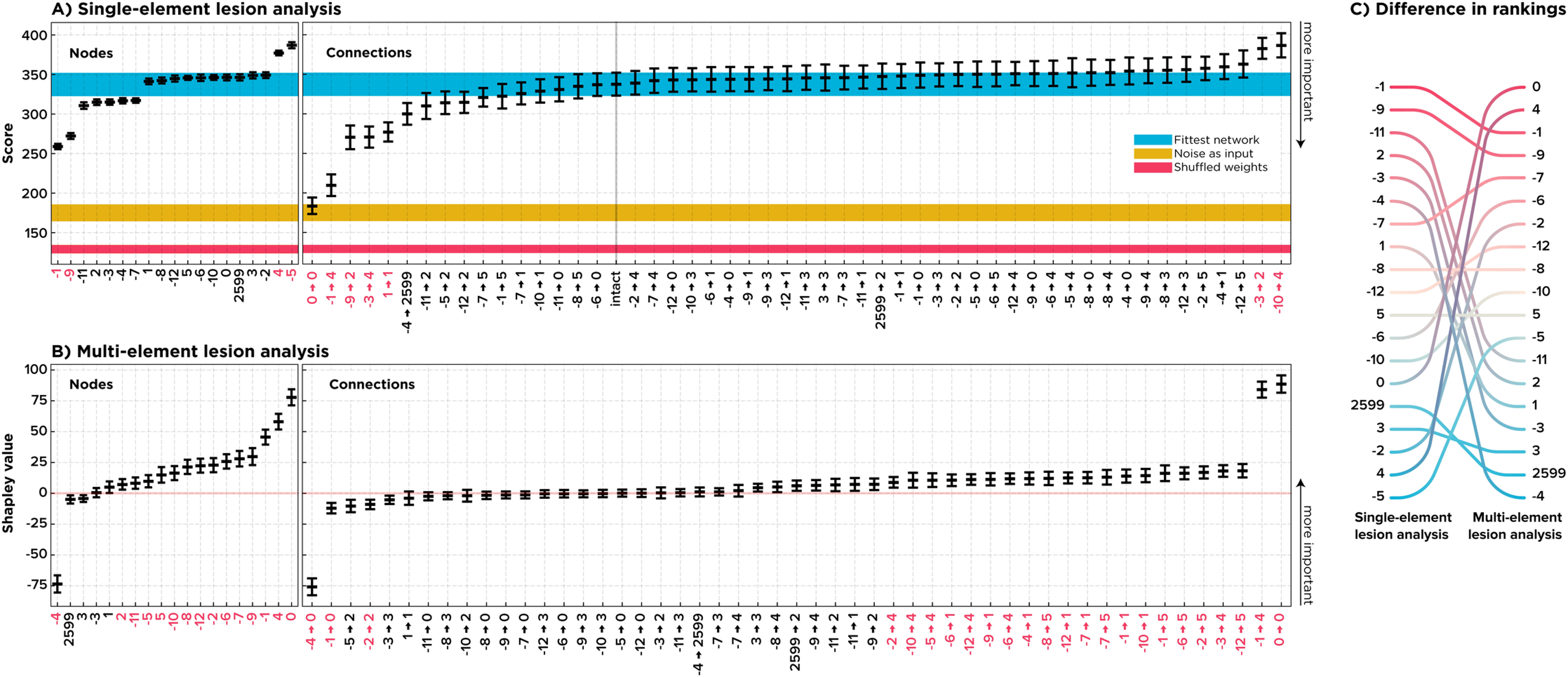

To overcome this issue, the authors compare their results to a multi-element approach.

Multi-element lesions in ANNs¶

In this multi-element approach, you sample combinations of lesions. For example, you silence node 1 and check the networks score, then silence node 1 and 2 together, 1, 2, 3 together etc. Then you calculate each nodes importance by comparing the networks score with and without the node in different combinations.

The results are shown as before in panel B, and in panel C on the right you can see that the single and multi-node ablations assigns different importance to different nodes. This and other results lead the authors to conclude that even small ANNs can be challenging to interpret. And so we should perhaps be cautious when interpreting manipulation results from larger and more complex systems. If you’d like to learn more about this approach and these results, we highly recommend the paper Fakhar & Hilgetag, 2022.

Figure 6:Silencing individual (A) or multiple (B) components of a trained neural network will lead to different conclusions on those components importance (C) Fakhar & Hilgetag, 2022.

- Lopes, G., Nogueira, J., Dimitriadis, G., Menendez, J. A., Paton, J. J., & Kampff, A. R. (2023). A robust role for motor cortex. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17. 10.3389/fnins.2023.971980

- Pastrana, E. (2010). Optogenetics: controlling cell function with light. Nature Methods, 8(1), 24–25. 10.1038/nmeth.f.323

- Fakhar, K., & Hilgetag, C. C. (2022). Systematic perturbation of an artificial neural network: A step towards quantifying causal contributions in the brain. PLOS Computational Biology, 18(6), e1010250. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010250