Introduction¶

This week is about learning. How it happens in the brain, what models we have, and how those models relate to algorithms from machine learning.

Before we get into the details, in this section we’ll start with an overview of what types of learning there are and the different mechanisms they could use.

What is learning?¶

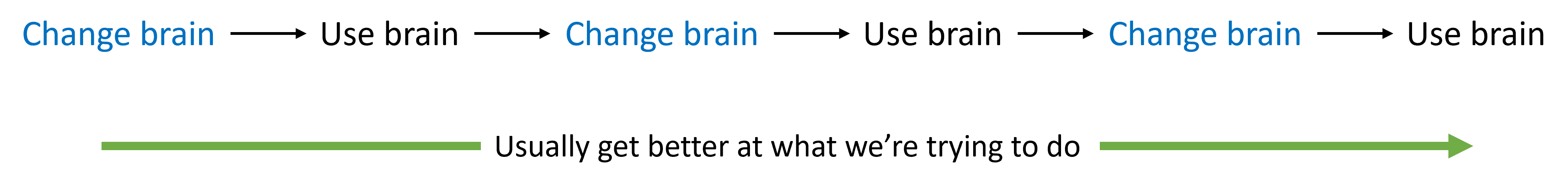

Abstractly what do we mean by learning? Something like: any change to behaviour in the face of experience. In other words, any change that leads to different behaviour can count and there’s a lot of things we could change in our brains.

Figure 1:What is learning?

Mechanisms¶

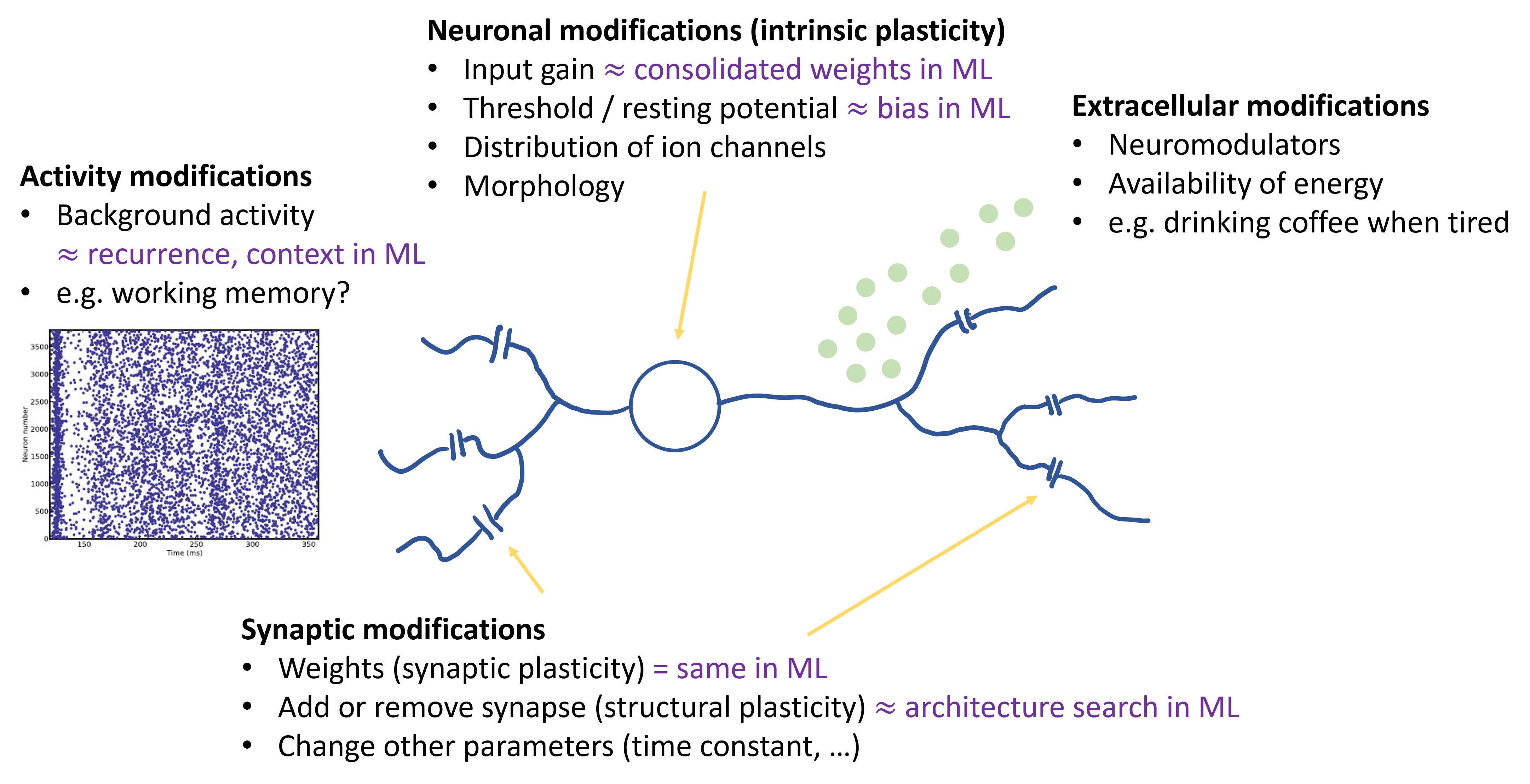

In principle, anything that modifies our behaviour could be a component of learning. We’re all familiar with the idea of modifying synaptic weights to change the function of a neural network. This is usually what is meant by learning in a machine learning context.

Although, there are some other things we can do with synapses too. We can add or remove synapses, which is sometimes referred to as structural plasticity or wiring plasticity - close to what you might call architecture search in ML. In principle, we might learn by changing any other aspect of a synapse, such as its time constants.

We could also learn by changing other properties of a neuron, such as its input gain, threshold or resting potential. These could be considered similar to changing weights and biases in ML. We could change the dynamics of the neuron and the way it integrates information by altering the distribution of ion channels across the cell membrane, or even its shape.

Another key thing that changes the behaviour of a neuron is the nature of its inputs, including the background activity of the network. Learning or memory doesn’t have to be stored in permanent changes to the structure of the neuron or synapses. Zero shot learning in language models using the context of the query could be thought of as fitting this pattern. In neuroscience, “working memory” is the things you hold temporarily in your brain in order to solve a task. A commonly held theory is that this is implemented by persistent patterns of activity in the brain and not by any permanent change.

Taking that further, the exact chemical composition of the extracellular regions of the brain changes the way neurons behave. Neuromodulators are diffuse chemicals that change the function of ion channels, and can be used by the brain to change the behaviour of large groups of neurons, such as dopamine. The brain could also choose to make more or less energy available, and by our behaviour we can directly change this chemical composition, like drinking coffee when you’re tired.

Categories¶

Let’s quickly look at some of the categories we need to keep in mind when discussing learning in the next few sections. One of the most important ideas is Hebbian learning, which we’ve seen before. This is often summarised as “cells that fire together wire together”. This can be seen as encouraging associative or causal connections in the brain.

One way to model this is with a family of rate-based models which use correlations in the firing rates of pre and postsynaptic neurons. Alternatively, we can take timing of individual spikes into account, as in spike timing-dependent plasticity or STDP.

If we’re thinking about ways the brain changes, then thinking about homeostasis is important. This is the process by which the body or brain keeps itself in a sort of balance. If some neurons are firing too much, then synapses might get weaker or thresholds might go up to reduce activity.

It’s also important to distinguish between short and long term changes, like the difference between changes in activity and permanent changes to the structure of synapses and neurons.

Finally, we should think about the signals available for learning, such as in machine learning we can distinguish between unsupervised and supervised forms of learning. Supervised learning in the way meant in machine learning might be sort of rare in the brain, as in there is no magic “you got it right” signal coming externally. Instead, we might think about various forms of self-supervised learning where one part of the brain gives feedback to another part. One example would be rewards. If you do an action and get a nice sugar treat as a reward, that’s a signal the brain can make use of. And of course, this leads into ideas around reinforcement learning.