Introduction¶

In the last section, we covered synapses, neurotransmitters, and receptors.

Hebbian learning¶

In general, we train artificial neural networks by adjusting their connection weights according to a learning rule, but what is the equivalent in biology?

As early as 1949 Donald Hebb proposed a relevantly simple learning rule:

“When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A’s efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased.”

At the time this was just a theory, but experimental evidence confirmed it around 20 years later.

This is often summarised as ‘Cells that fire together wire together’, and conversely ‘Cells that fire out of sync lose their link’.

Though this misses the fact that cell A must spike first to contribute to B’s firing, therefore the relative timing matters.

Spike timing-dependent plasticity¶

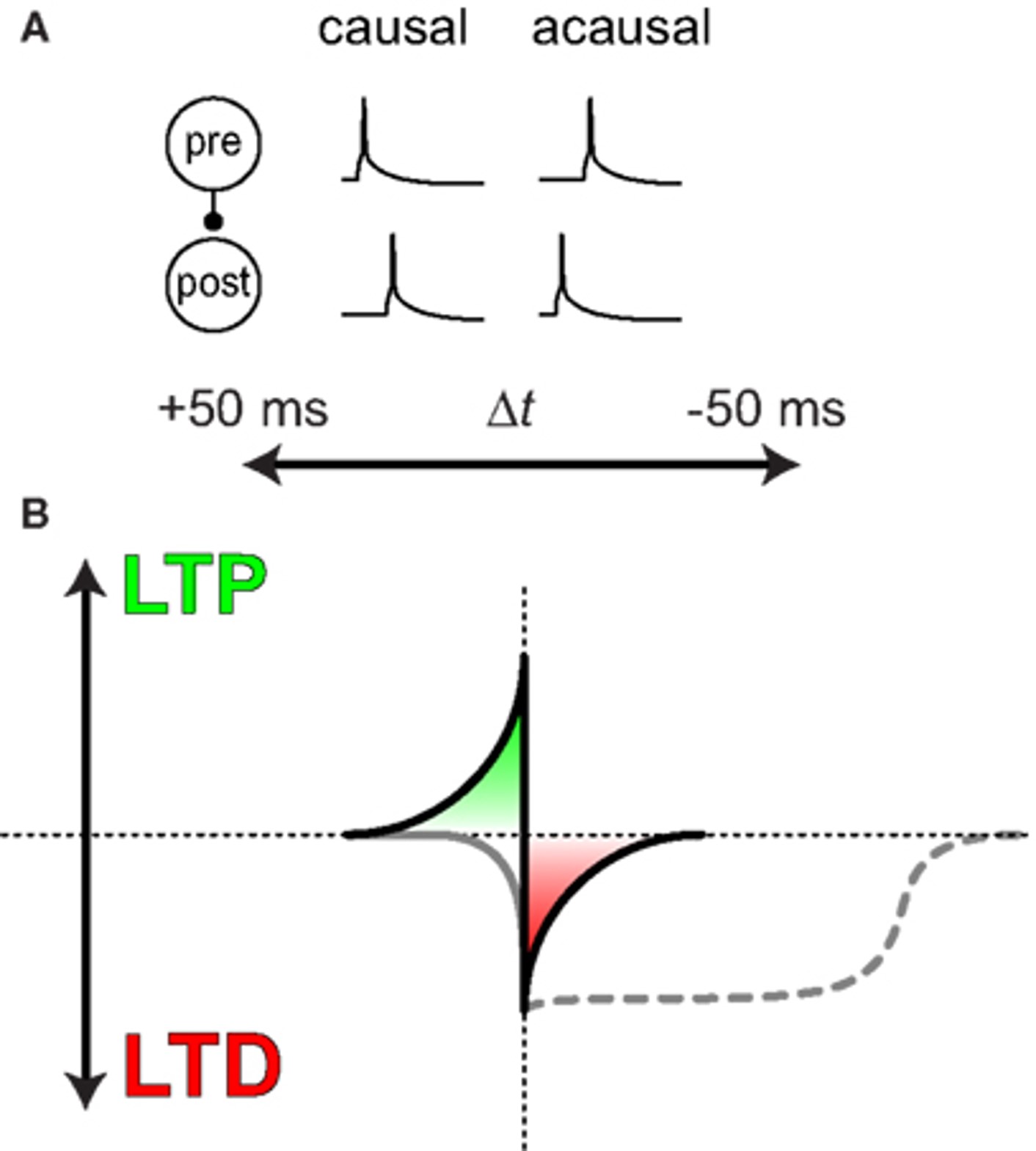

Let’s consider a pair of neurons. In the figure below, panel A illustrates that if the pre-synaptic neuron’s spike occurs before or after the post-synaptic neuron, their relationship is causal or acausal.

Panel B shows how this synapse’s strength (on the y-axis) will be adjusted depending on the difference in spike timing between the two neurons. If the relationship is casual, so ‘pre’ precedes ‘post’ the strength will be increased or potentiated (shown in green). While if it is acausal, so ‘pre’ tends to follow ‘post’, then the strength will be decreased (shown in red).

Figure 1:Spike timing-dependent plasticity Markram, 2011.

This is known as spike timing-dependent plasticity, and it tends to induce long-term changes in synaptic strength via processes known as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long term depression (LTD).

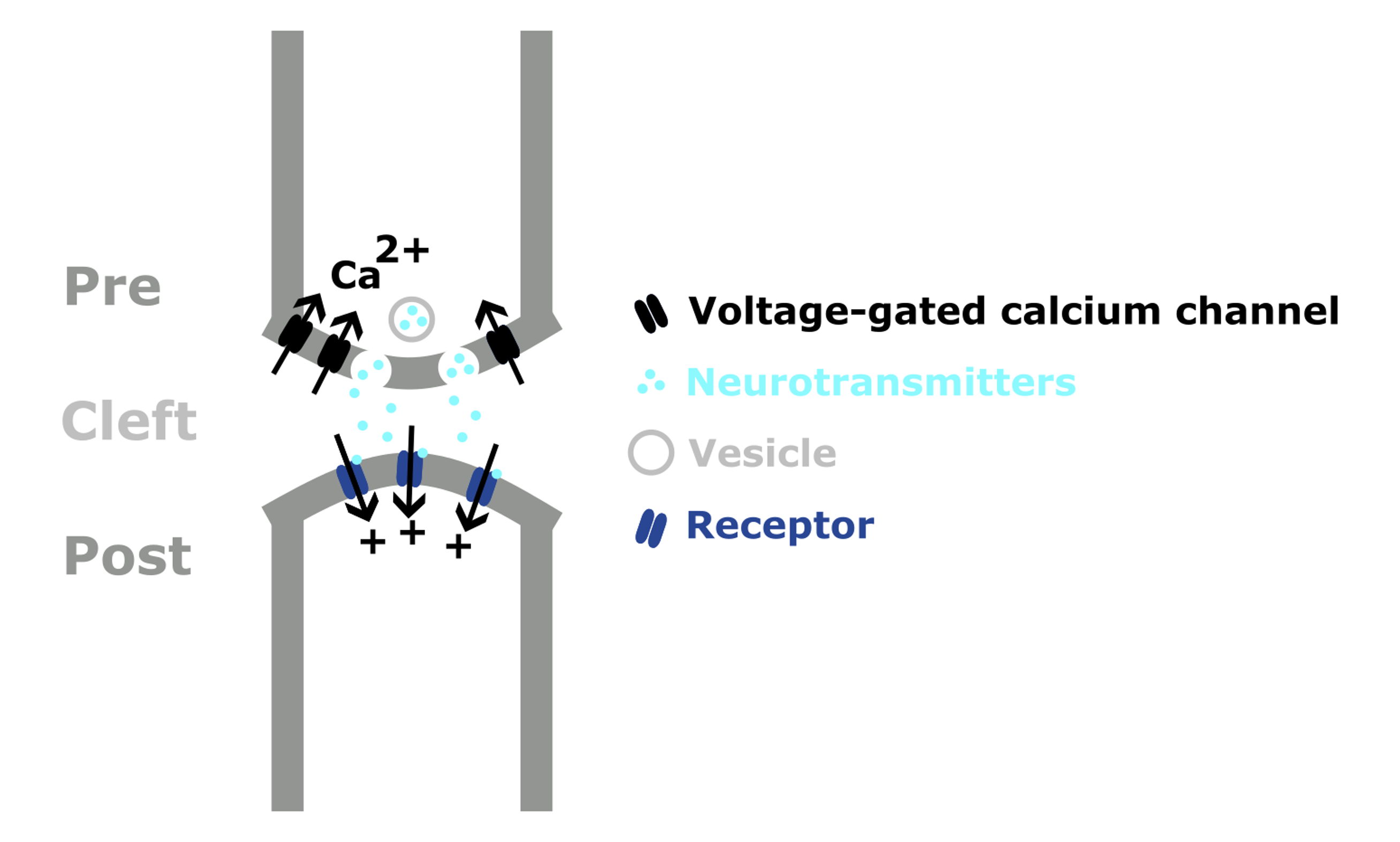

So, what changes at the synapse to cause this change in weight?

Altering synapses¶

If we think about the structure of the synapse, then we can see that there are many possibilities for changing the connection strength, such as:

- Increasing the number of synaptic vesicles or density of neurotransmitters.

- Increasing the number of post-synaptic receptors.

- Increasing the surface or even adding an additional synapse between the two neurons.

But these are long-term changes, and synaptic weights can also change on much quicker timescales, on the order of hundreds to thousands of milliseconds. This is known as short-term plasticity.

Figure 2:Schematic diagram of a chemical synapse.

Short-term plasticity¶

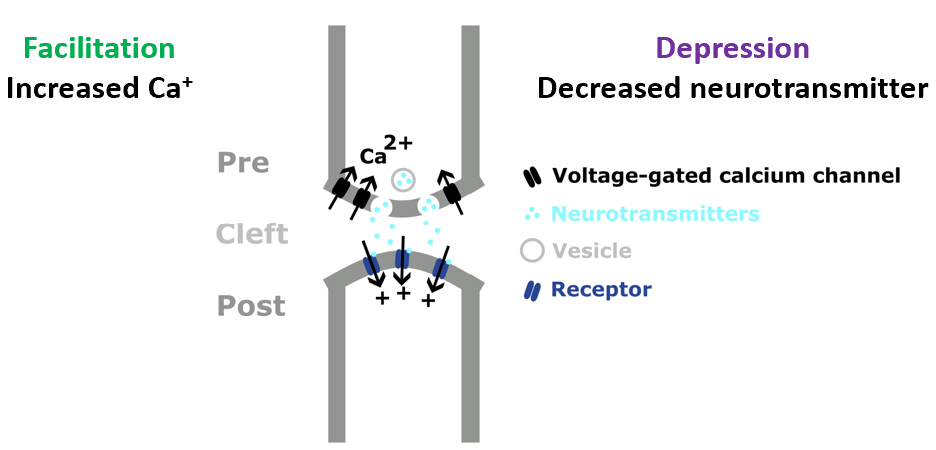

Short-term plasticity describes how synaptic strength dynamically changes with the level of presynaptic activity. Broadly, short-term facilitation is caused by the higher levels of calcium at the axon terminal after spiking, which increase the probability of neurotransmitter release.

Short-term depression is caused by the lower levels of neurotransmitters available at the synapse, and in an extreme case, it’s possible that the synapse will fail to send a signal at all.

Hence, short-term plasticity shows how a neuron’s recent activity and the state of it’s synapses influence it’s weight dynamically.

The fact that synapses will sometimes fail to send a signal may remind you of drop-out in machine learning, though in this case, individual connections are failing, not the entire unit. Yann LeCun and colleagues explored this difference in a paper discussed below Wan et al., 2013.

Figure 3:Short-term facilitation and depression at a chemical synapse.

DropConnect¶

Just to be explicit:

- Dropout - randomly silence units during training, which reduces over-fitting.

- DropConnect - randomly silence (i.e. set to zero) weights.

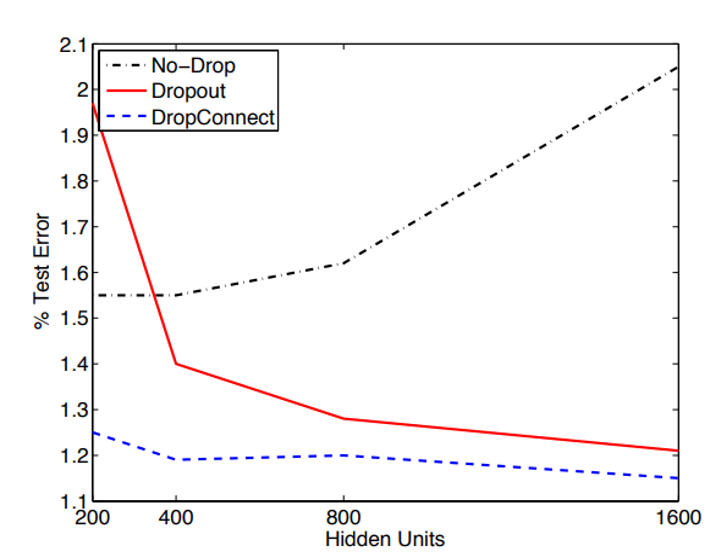

Just to give you a quick comparison between the two, the graph below shows the test error on MNIST as a function of the network size, with the following lines:

- No-Drop (black) - the error increases with size as the network increasingly overfits the training data.

- Dropout (red) - the error decreases with size.

- DropConnect (blue) - the error is lower and more stable.

Figure 4:Test error as a function of network size for network’s trained with Dropout (red), DropConnect (blue) and neither (black). From Wan et al., 2013.

For more!

Wan et al. (2013) provides more empirical and theoretical results which suggest that DropConnect may be advantageous.

- Markram, H. (2011). A history of spike-timing-dependent plasticity. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 3. 10.3389/fnsyn.2011.00004

- Wan, L., Zeiler, M., Zhang, S., LeCun, Y., & Fergus, R. (2013). Regularization of neural networks using dropconnect. Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning - Volume 28, III-1058-III–1066.