Introduction¶

Last week, we covered how ionic movements enable neurons to generate their resting membrane potential and spikes.

Saltatory conduction¶

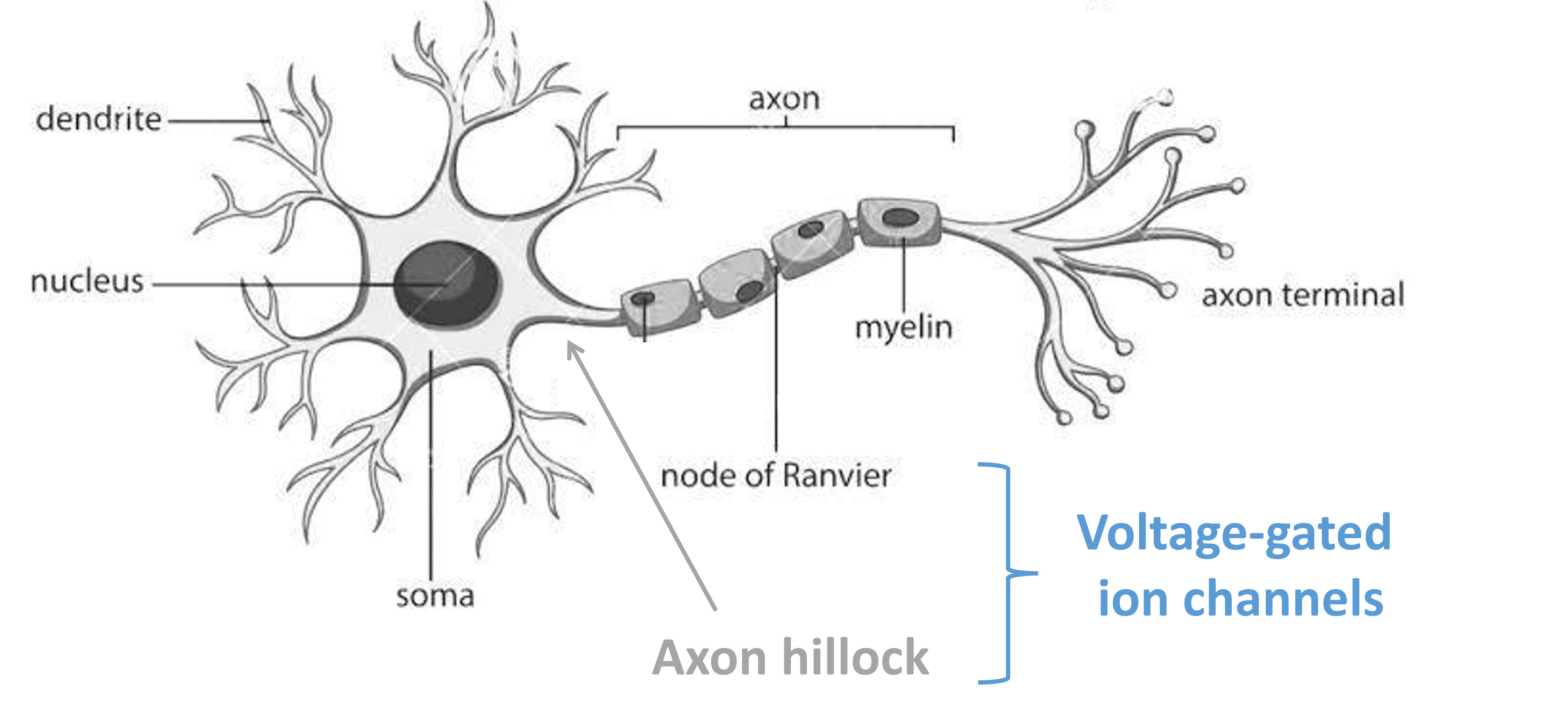

Inputs at the neurons dendrites cause sodium channels to open.

Following their concentration gradient, these ions diffuse into the cell, and spread along the dendrites to the soma and the axon hillock - an area rich with voltage-gated channels.

Low amounts of input won’t raise the membrane potential enough to trigger the opening of these channels (remember the gate threshold from last time), but large amounts of input may, in which case more sodium will flow into the neuron and then begin to diffuse down the axon. However, without any help, this signal would dissipate and be lost as it travels the length of the axon.

The solution to prevent this, is to insulate the axon using a fatty substance called ‘myelin’. However, even insulating the whole length may not be enough, so instead, there are blocks of myelin separated by gaps known as ‘nodes of Ranvier’.

These nodes of Ranvier are rich in voltage-gated channels. So, effectively boost the signal as it travels along the axon and generate ‘saltatory’ or jumping conduction.

Figure 1:Schematic diagram of a single neuron.

So what happens once this signal reaches the neuron’s axon terminals?

Chemical synapses¶

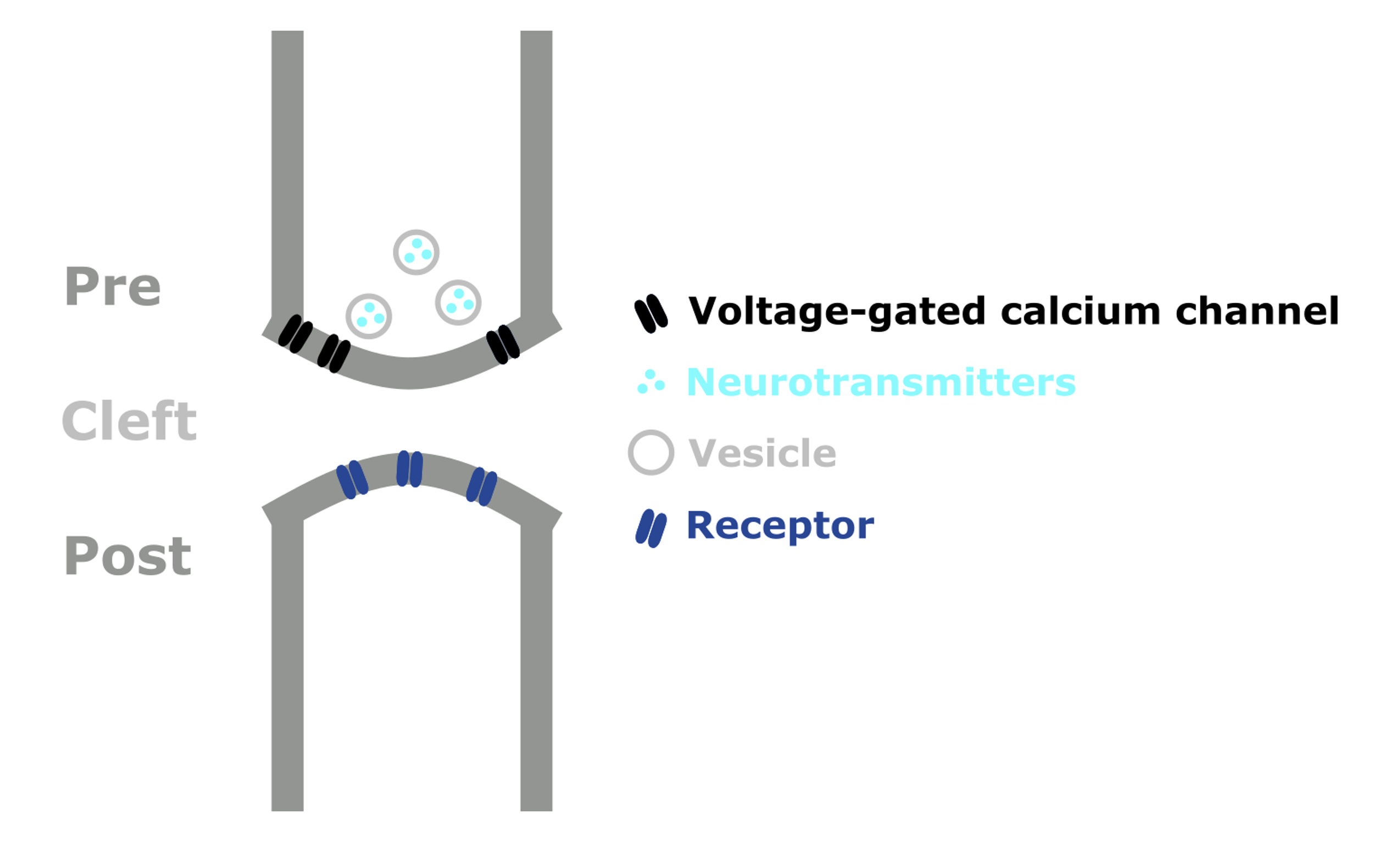

If we zoom into on one of these terminals, we can see that this is where our neuron connects to another adjacent neuron.

This connection is called a ‘synapse’, and the neurons on either side of the synapse are called the pre- and post-synaptic neurons. These connections can either be electrical (known as gap junctions), or chemical (like the one shown in Figure 2).

So what makes up a chemical synapse?

The pre-synaptic neuron has vesicles, 3D spheres, filled with chemical messengers known as ‘neurotransmitters’. The post-synaptic neuron has proteins embedded in its membrane, known as receptors, which the neurotransmitters bind onto.

The gap between the two is known as the ‘synaptic cleft’. While it is often drawn like a gap, there are actually proteins which reach across the cleft and hold the junction together.

Figure 2:Schematic diagram of a chemical synapse.

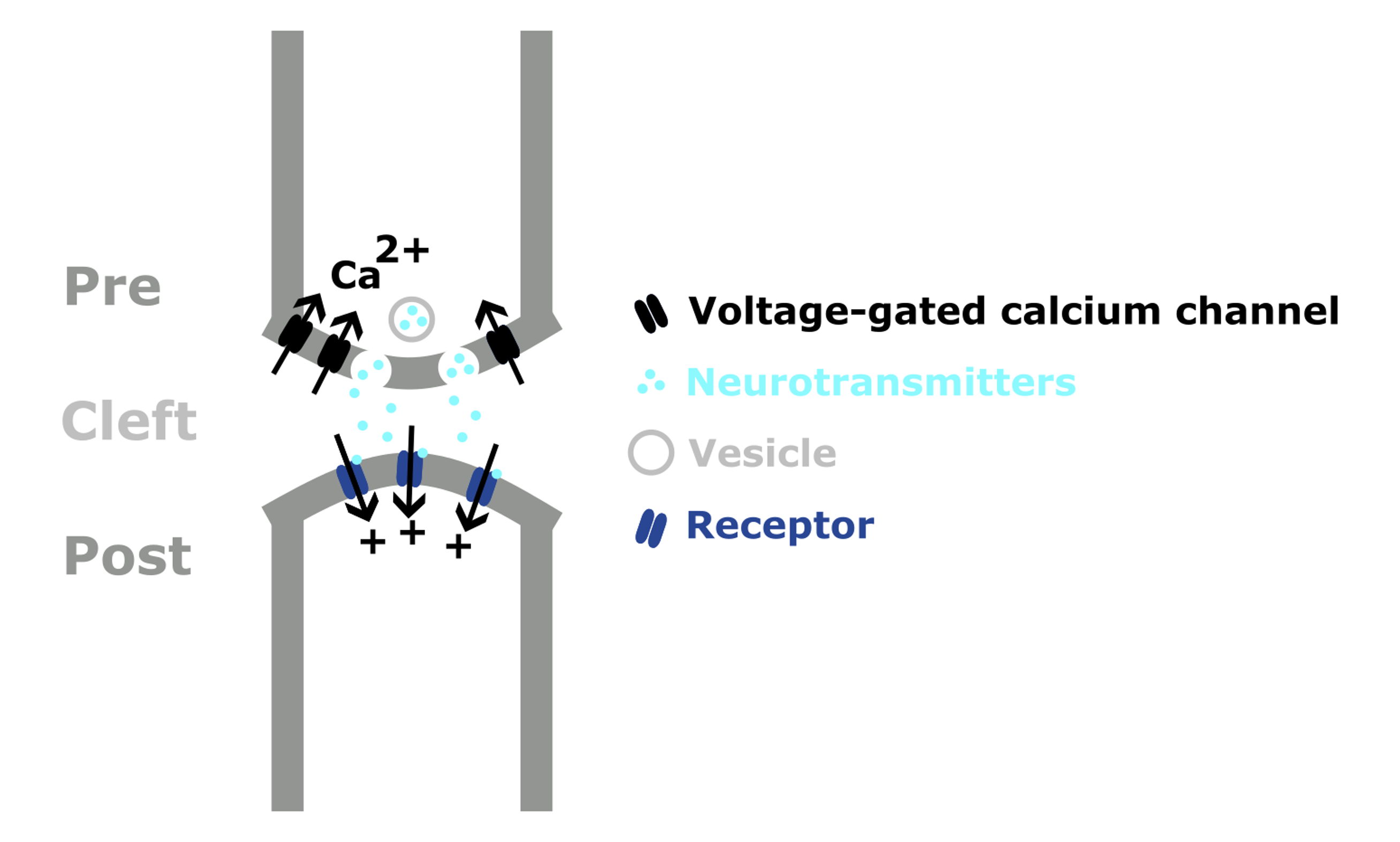

When an action potential reaches the axon terminal, the influx of ions depolarizes the membrane and causes voltage-gate channels to open, allowing calcium to flow into the cell. This causes the synaptic vesicles to fuse with the cell membrane and release their neurotransmitters into the cleft.

The neurotransmitters then diffuse across the cleft and bind to the post-synaptic receptors, triggering different effects. As shown in Figure 3, binding causes an ion channel to open and positive ions to flow into the post-synaptic neuron, raising its membrane potential.

This is known as an excitatory synapse, as a pre-synaptic action potential will make the post-synaptic neuron more likely to fire a spike. Conversely, inhibitory synapses reduce the post-synaptic neuron’s membrane potential, making spiking / action potentials less likely.

This signal terminates when neurotransmitter molecules:

- Diffuse away from the cleft.

- Are broken down by enzymes.

- Are taken back up into the pre-synaptic neuron.

Figure 3:Schematic showing neurotransmission at an excitatory chemical synapse.

Neurotransmitters¶

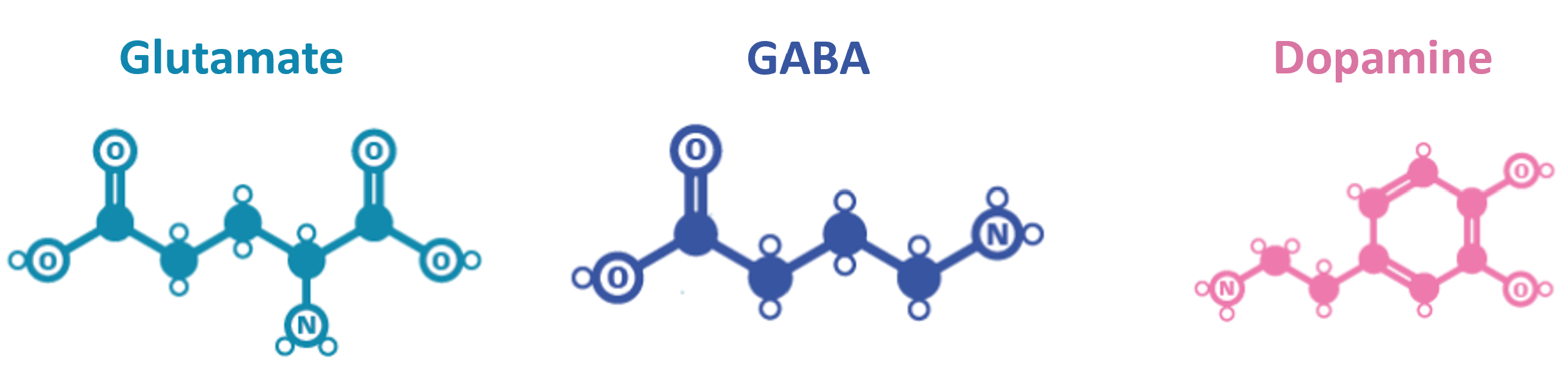

Neurotransmitters are molecules synthesized by neurons, which are used to signal to other neurons. There are hundreds of neurotransmitters which are thought to have different functions. Here are 3 examples:

- Glutamate - the main excitatory neurotransmitter in vertebrate nervous systems.

- GABA - the main inhibitory neurotransmitter.

- Dopamine - often thought of as a pleasure signal, but it’s probably best described as a signalling valence.

Individual neurons tend to contain and release multiple transmitters. For example, a single neuron may use both GABA and Dopamine. Though in general, neurons release the same set of transmitters at all of their synapses. This is known as Dale’s principle.

Figure 4:Chemical structure of glutamate, GABA and dopamine (Adapted from).

Dale’s principle¶

Dale’s principle sets up an interesting contrast between biological and artificial neural networks. Biological neurons release the same set of neurotransmitters to all of their partners.

However, in artificial neural networks, single units have both positive and negative output weights, allowing their activation to send different signals to different units.

So, is this a limitation of biology or an advantage?

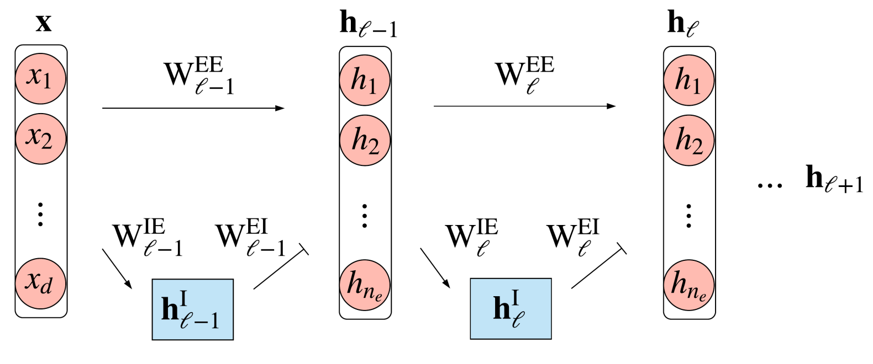

To explore this question, Cornford et al. (2021) built ANNs in which each unit was either excitatory or inhibitory. Shown below in pink and blue.

Figure 5:ANN model respecting Dale’s principle. FromCornford et al. 2021.

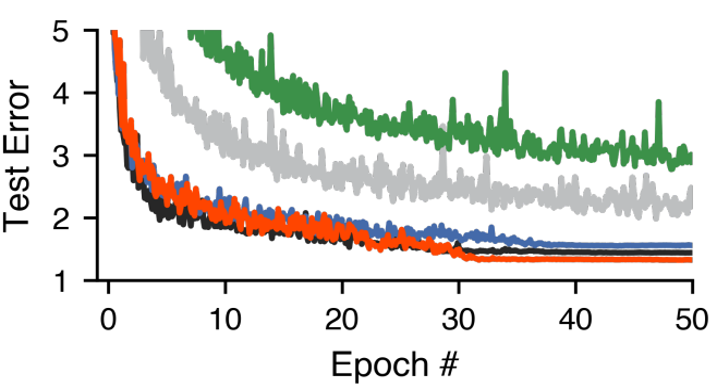

It turns out that these networks are difficult to train with standard gradient descent, and end up performing worse than a standard ANN. You can see this on the graph below, where the black curve shows the performance of a standard ANN and the green shows a simple implementation of Dale’s principle. So, they introduced some corrections and were able to get networks which respect Dale’s principle and match the performance of standard ANNs. This improved implementation of Dale’s principle is shown in red.

Figure 6:Test error over training, for: standard ANNs - black, a naive-implementation of Dale’s principle - green and an improved version - red. From Cornford et al. 2021.

But, as they’re only able to match standard ANNs, and no one has shown better results by following Dale’s principle. Why neurons tend to follow Dale’s principle remains an open question.

Receptors¶

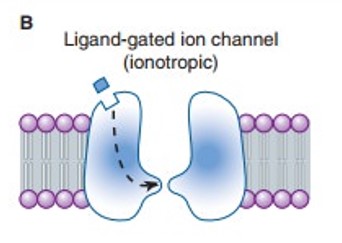

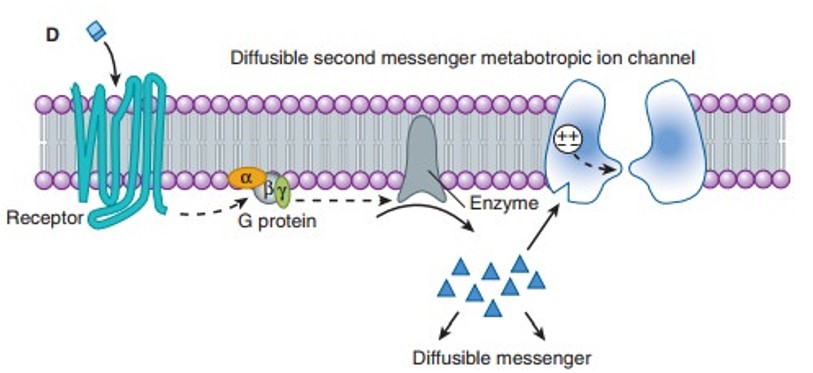

Once released, neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft, bind receptors embedded in the cell membrane, and trigger effects. There are hundreds of receptors which are specific to different neurotransmitters, but there are just 2 major types:

- Ionotropic receptors - receptors where neurotransmitter binding triggers a change in structure, causing an ion channel to open.

- Metabotropic receptors - receptors where binding triggers signalling cascades within the post-synaptic neuron, which may open ion channels or cause other effects.

Hopefully this has given you a better idea of how synapses work. In the next section, we’re going to cover how synapses can adjust their strength or weight, and a few other details.